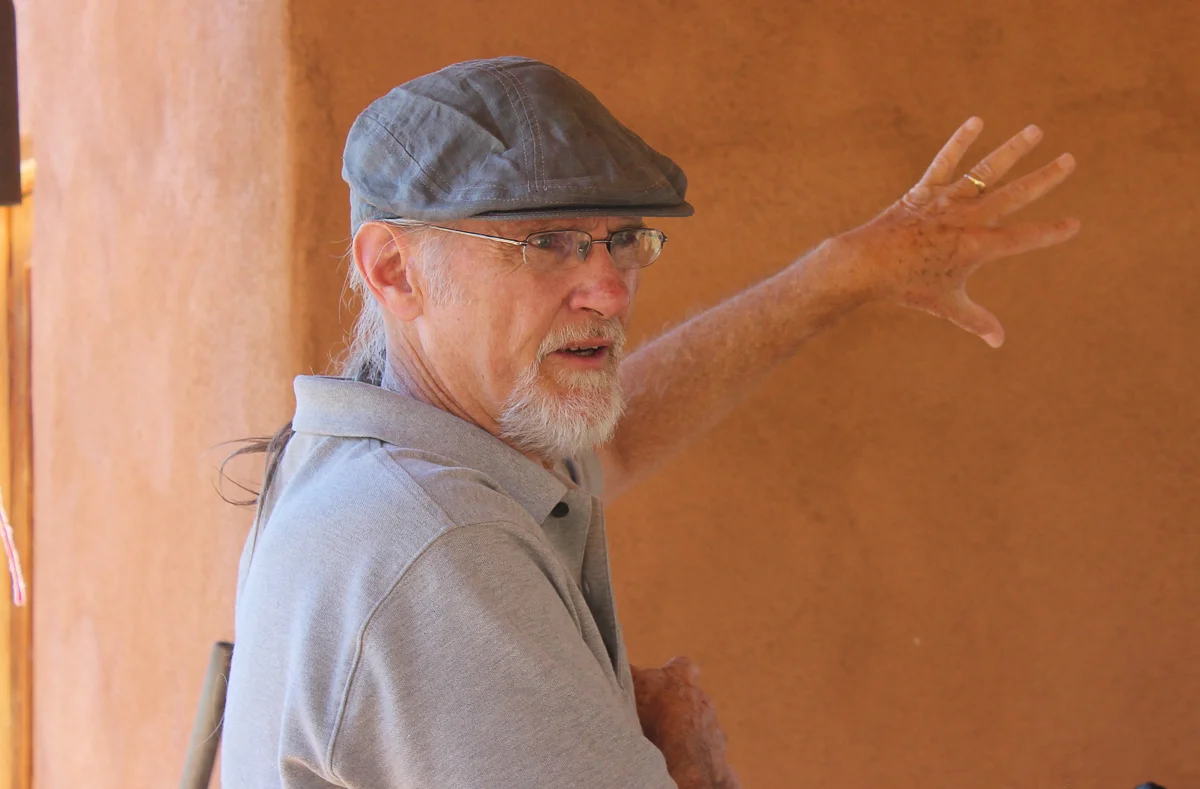

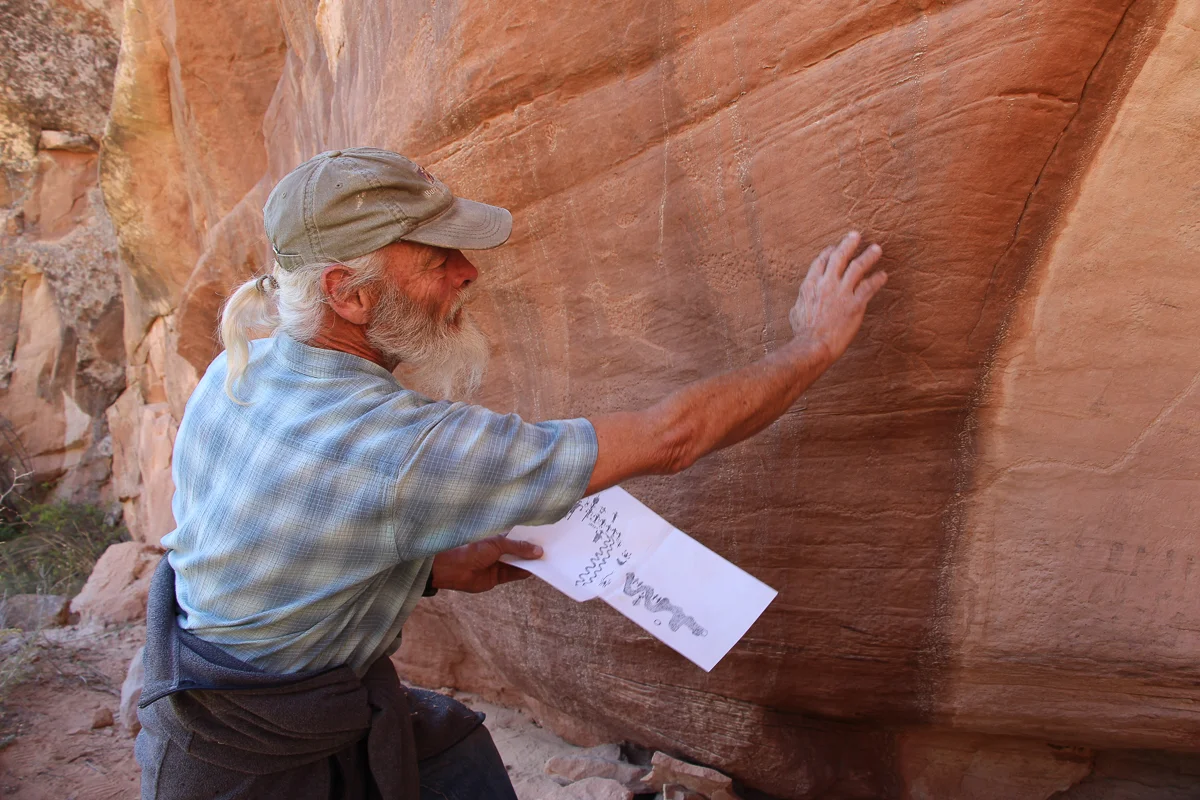

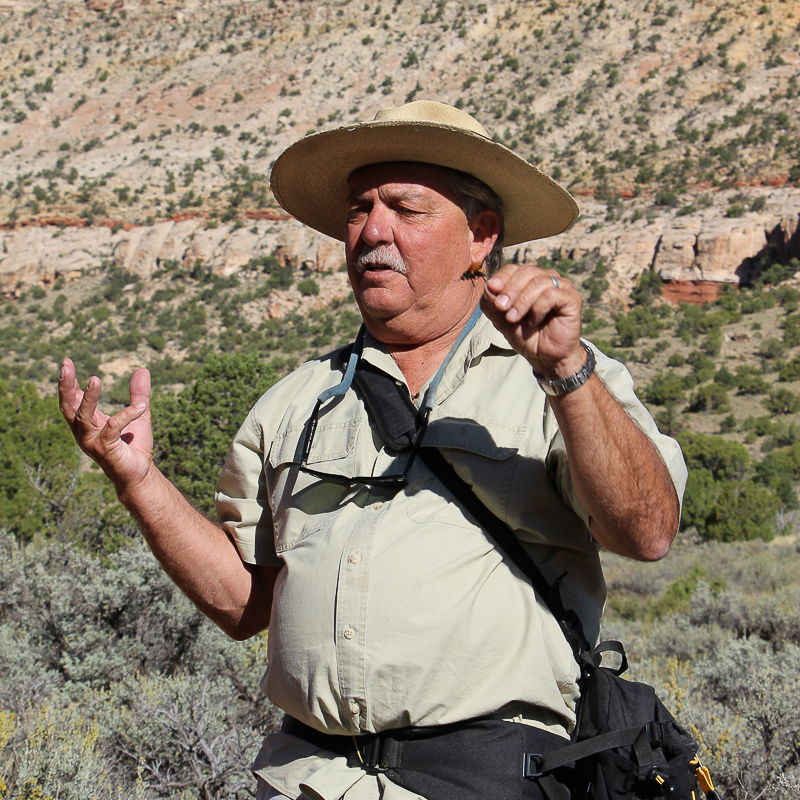

As an ecologist, Paul Arbetan reads landscapes like others might read a graph: processing the information his eyes show him and analyzing the patterns of terrain and vegetation. On a hike in the rocky hills surrounding Santa Fe, New Mexico, Paul stops the Westies trailing behind him and points to a patch of earth seemingly indistinguishable from its neighbors. Upon closer examination you can see the faint remains of hoofprints in the bare soil, and he explains, “Blowout; overly grazed spot. Look at the way the grasses are. What happened to all this soil?” Observations and questions like these are a main component of the two-week-long field biology course that Paul teaches to Semester in the West. This segment takes the group on a tour through the beautiful, rugged, and diverse desert ecosystems of New Mexico with the foundational goal of giving Westies “a sense of why things are the way they are across a landscape.”

Paul’s connection to the program began when he was attending Lawrence College in his home state of Wisconsin where he became good friends with a politics student named Phil Brick. After four years of spending their weekends whitewater kayaking down the rivers of the Midwest, the two went off to pursue different careers. Phil eventually became a professor at Whitman College while Paul studied evolutionary ecology and population genetics. Today, Paul works as a consulting biologist. With clients such as the Department of Military Affairs and the Bureau of Land Management, his projects include everything from creating plans to remove invasive species to researching the biological impact of army training exercises. Paul’s motivation to do this kind of work stems from his passion for ecology and the natural world, or as he put it simply, “I like seeing country…[I] like understanding country. [I] like seeing the relationships across a landscape."