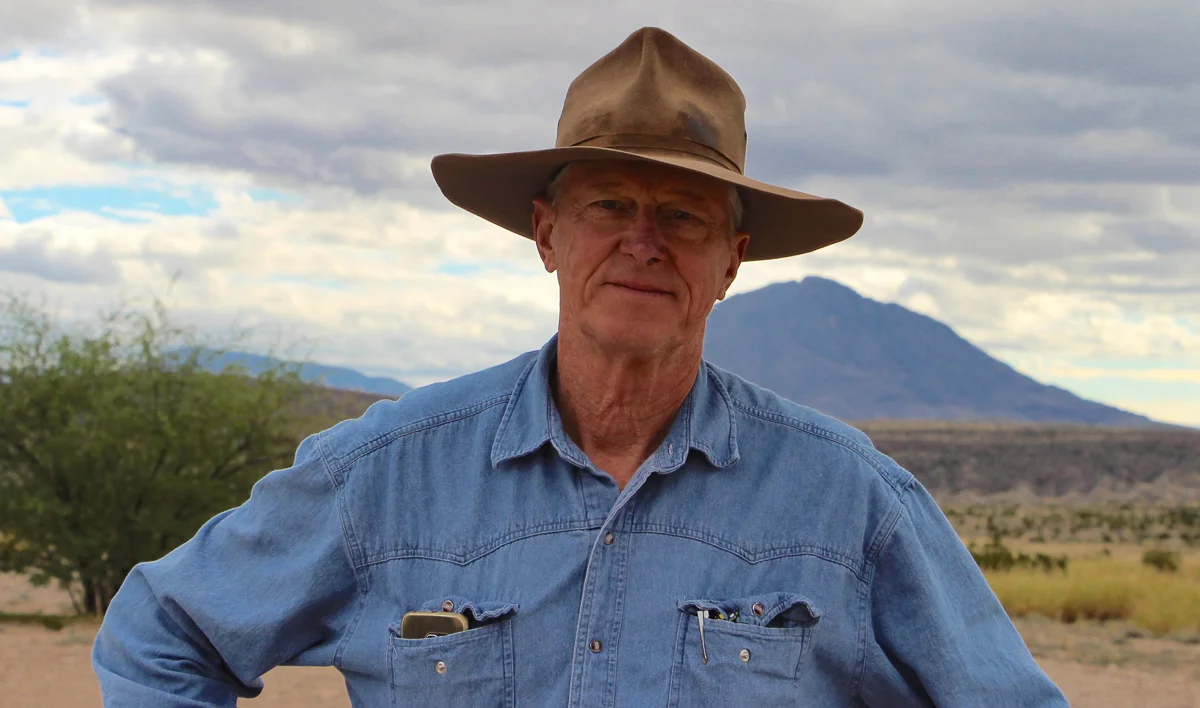

In the grand web of environmental conservation, Ray Bransfield has found his niche. Bransfield is a Senior Biologist for the Palms Springs Department of Fish and Wildlife, where he has served for the past 33 years. He works under a specific section of the Endangered Species Act to assess the environmental impacts of and put holding actions on prospective development projects in order to keep threatened species from sliding past the point of return. Bransfield’s primary focus is the desert tortoise. When he thinks about the tortoise, whose population in the Mojave Desert is struggling to survive due in large part to industrial developments and collisions with highway and off-highway vehicles, he reflects on the importance of preserving a world where the tortoises are still there for the next generation. For Bransfield, it is not just about the desert tortoise though, but also about maintaining the biodiversity of the Mojave Desert and keeping wild places everywhere.

Bransfield focuses on the positive things he can do for the tortoise, and aims to best use biology, the law, and cooperation with people from all sides to protect ecosystems and endangered species. He affirms that at times the legal system is an important aspect of achieving conservation goals, and also believes that education is a critical piece to this puzzle. If the public appreciates and cares for their desert ecosystems they will decrease activities that threaten habitat and demand that companies take responsibility for protecting the environment.

By Abby Popenoe