It's been a wild ride for Semester in the West's 2016 program. This fall we covered over 11,000 miles, traveling further north (Twisp, Washington), south (Big Bend National Park, Texas) and east (Pine Ridge, South Dakota) than any previous program. The last few months have flown by and now we find ourselves back where we started at the cozy lodges of the Johnston Wilderness Campus. As the Tech Manager, it gave me particular pleasure during Thanksgiving to meet so many of you who have been following along on our trip virtually. As a thank you and a personal sendoff, I hope you enjoy this final camp life series of 2016. Tune back in come 2018 for more photos, speakers and stories produced by a whole new crop of Whitman's brightest minds.

Sincerely,

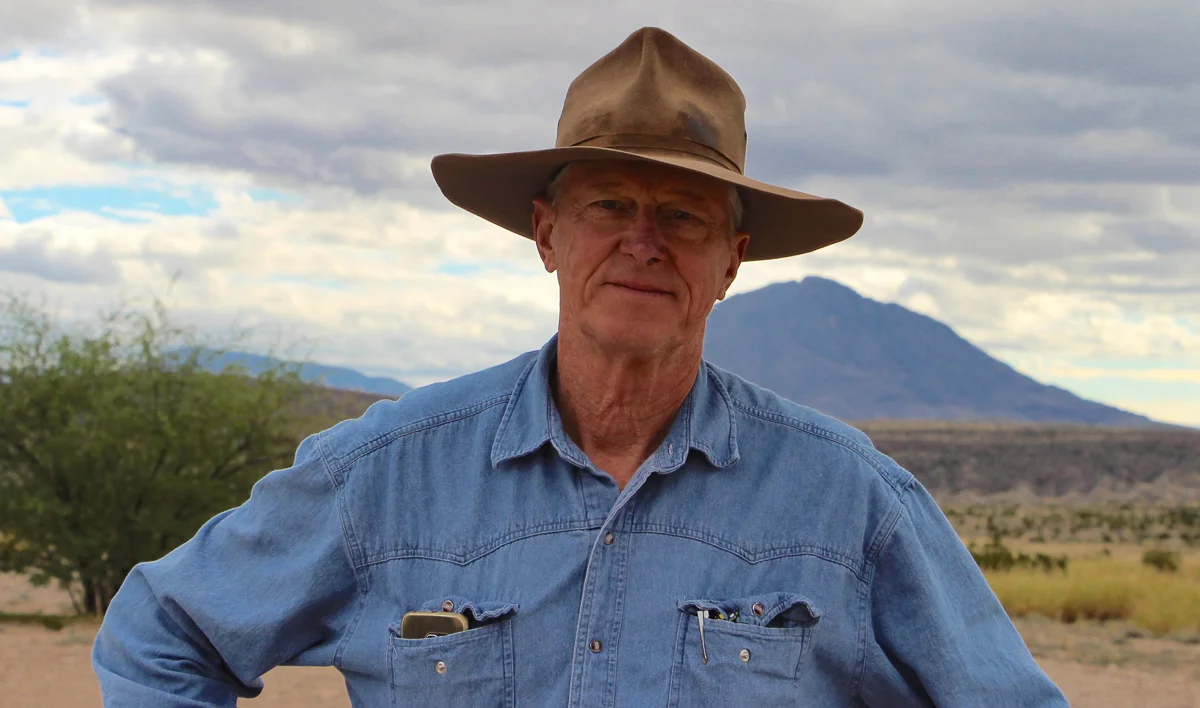

Collin Smith

Technical Manager 2016