Sacred Datura

A hawk moth moves through the summer sky, his brown and pink wings slicing through the fog of a simmering evening in Castle Valley, Utah. Unlike the dozing mule deer and dozens of pinyon jay that flock to their nests overhead, the hawk moth’s night is only beginning. He flits his way through evening primrose and around the spines of a prickly pear, making his way to the heady, sweet scent of a white bud on the verge of blooming. Hovering like a hummingbird, he waits for the slow, slow opening of his favorite blossom; the Moonflower.

This bloom is as beautiful as its name, spiraling out from its trumpet-like center as if reaching out, calling to any passerby to stop and sit with it for a moment. Each flower is a delicate, ephemeral thing, only opening to soak up the light of the moon for one night before slumping limply on its stem. This particular plant, nestled beside a patch of purple aster, is low and winding. Velvety green leaves sprawl from a purple stalk that roots in loose, disturbed soil, drawing water up from deep taproots. Its leaves bear visual evidence of its close relationship to the Hawk Moth, riddled with lace-like holes made by the mouths of tiny larvae. There's something enticing about this plant, a soft, cool vision in the harsh oranges and browns of Castle Valley. Yet, like the thorny seed pods concealed beneath its teardrop-shaped leaves, there's a danger lurking under its sweet scent and pearly blossoms.

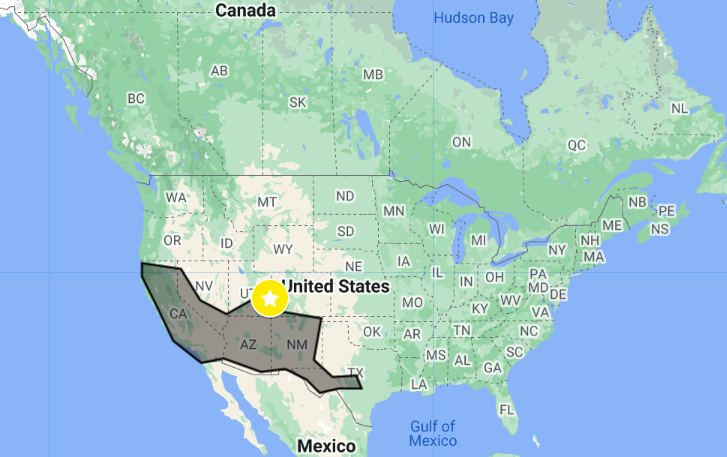

No one knows this danger better than the tiny Hawk Moth, who flocks night after night to the Moonflower, or Sacred Datura. The nectar of this plant is not only sustenance for him, but an addiction that keeps him enthralled. Hailing from the same family as nightshade and mandrake, Datura contains toxic alkaloids such as hyoscyamine, atropine, and scopolamine, making it a lethal snack for most inhabitants of the Moab desert. The leaves, flowers, roots and even seeds of the Datura plants contain these chemicals, giving them folknames like the Devil’s Work and Mad Apple. But some animals, like the Hawk Moth, have developed a delicate truce with the toxins, flirting with death in order to experience their intense hallucinogenic effects. Though he enjoys the Evening Primrose and Colorado Four O’Clocks that bloom nearby, it's Datura's narcotic high that the Hawk Moth is waiting for, beating his wings impatiently over the late-blooming flower. In exchange for its intoxicating nectar, he will bumble drunkenly from flower to flower, spreading pollen and propagating more Datura. Though this plant found its way to Castle Valley by human hands, traveling from a native plant nursery to find its home in the red soil of the valley floor, a small, younger plant about fifteen feet from where the Hawk Moth hovers is evidence of this pollination scheme’s success.

Moths are not the only ones who have learned to benefit from Datura’s chemical effects. Three-lined potato beetles use the poison as a defense, eating leaves and then covering themselves in their excrement to ward off predators. Humans, also, have used the plant for generations, both as a potent ritual drug and simple decorative addition to their gardens. These relationships speak to the complicated nature of the Datura. There’s a duality to be found in almost all aspects of this plant. Soft petals grow right beside prickly seed-pods and fragrant flowers stem from acrid-smelling stalks. The hallucinations it causes are often frightening and dangerous, but it has played an important role as a sacred healer and ritual enhancer for countless human cultures. Even its relationship to the Hawk Moth is contradictory. On one hand, it seems to take advantage of the moth, forcing a dependence in order to ensure pollination. But it also provides sustenance and shelter for the moth’s young, letting them feed on its leaves as they grow. It is not entirely a helpful plant, but neither is it an entirely harmful one. Like much in the desert, it carries both the promise of beauty and danger, abundance and death.

As the petals of the Moonflower finally open, though, its becomes hard to remember anything besides its beauty. The Hawk Moth, his patience rewarded by the slow bloom of this desert flower, unfurls his long tongue and takes a cool drink in the evening sun. He brushes some of the pollen on his head against the flower's stigmata as he lingers, fulfilling his role as the Datura’s primary pollinator. Satisfied and drowsy, he buzzes away to enjoy his high, leaving the white blossom in silence. Its petals held high against the setting sun, it begins its singular night of full, fragrant life in the Castle Valley stillness.

By Hannah Cuvin