The Curlycup Gumweed Loudly Proclaims: “Chew on this!”

Curlycup Gumweed (Grindelia squarosa)

Oh, what a wonderful thing for such sweetness to grow out of such corruption, for yellow petals to reside among blackened tar, for a green sticky bulb to arise from abandoned asphalt. One may see a healthy bunch of Curlycup Gumweed, capitalizing off the uninhabited soil underlying the hard concrete road, emerging through snaking cracks, unphased by the hurling motor vehicles mere inches away. Upon seeing this plant, on a roadside, vacant lot, or pasture, someone may exclaim, “You see, silly! We aren’t doomed; plants thrive on our industrialization!” Amidst the scorched remnants of natural fire or among the monotonous cheatgrass of a poorly managed rangeland, the Curlycup Gumweed grows out of disturbance, sprouting where no other vegetation has the chance to.

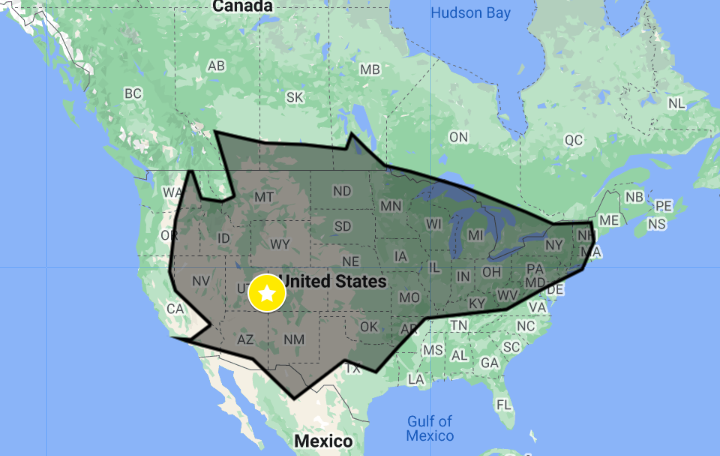

This is not to say that Curlycup Gumweed can’t also be a product of soft soil cultivated by loving hands, as it is on 270 Pope Lane. Its condition of growth is almost as expansive as its native range, spanning most of western and southwestern North America. Here, it is speckled in bunches amidst an array of native and non-native species that have been intentionally placed or fortuitously found on this plot at the base of Castle Valley. While the vibrant growth on this land lies in opposition to the pale plains of cheatgrass that Curlycup is often associated with, it flourishes here, too. However, its success may not be evident in late September.

Today, its leaves are dry and cracking, twisting around itself, its flowering season is coming to a close. Weeks prior, you may have seen one of the 40 species of native bees it hosts hopping from a neighboring Showy Milkweed to the Gumweeds inflorescence, indulging in its glucose-heavy nectar. Its flower heads are the size of buttons, runtish as compared to their more acclaimed siblings in the sunflower family. The buds that haven’t already shriveled and browned are mostly pedal-less; only a few of its tops still shine yellow and flicker in the pounding Utah sun.

While its bright yellow petals on top are readily depleting, its sticky, green, leaf-life, bracts are largely intact. Protruding in short tendrils that curve downward, they exude gummy resin. While this resin releases a sweet aroma, it is unpalatable to grazing insects who would otherwise see the weed as an addition to the herbaceous feast 270 Pope has to offer. It is not only insects that are deterred, but also creatures much larger. The Gumweed absorbs copious amounts of selenium from the soil, a chemical that is poisonous to ungulates. To this point, the same someone who took Gumweed to be a testament to the fallacy of climate change, may also exclaim; “Grazing can’t possibly be that detrimental to public land, look at this wonderful native plant left in abundance!” They have unfortunately failed to notice the myriad of other native grass and weed species that have been devastated by livestock. Capable of concentrating selenium 500 times the concentration of the soil, the Curlycup Gumweed simply got lucky in the face of cattle herds.

Its sticky resin coating also allows the plant to absorb the UV-B spectrum from the sun, ensuring that its shadeless basking doesn’t lead to scorching. This absorption of the sun is not only a form of protection but of production the UV-B rays catalyze further secretion of resin. However, the resin doesn’t protect the plant from the increasingly colder days.

This seeming finale to a vibrant life, may or may not be deceiving. Curlycup Gumweed can be both biennial and perennial. If this particular plant is biennial, the closing of this flowering season may also be the closing of its two-year life span. However, it is possible that this Gumweed is a short-lived perennial, growing back a year or so more as its roots stay locked beneath the soil during months in which it’s too cold to be anywhere else. Its roots are both shallow and can extend deep - more than six feet - within the soil, stretching itself out from a short, vertical, rhizome. This extensive root system collects and maintains moisture, allowing the plant to withstand long stretches of drought.

Even if it’s the end for this particular plant, wedged next to a swaying Apache Plume, it has creatively ensured its future reproduction. One flavor of seed just isn’t enough for this resistant sunflower. Its seeds cluster to comprise the center of the flower head, as well as rim the perimeter at the base of its delicate petals. The center disk’s seeds germinate more quickly while those from the outside can hold longer in the soil, allowing germination to occur in different seasons and conditions. A gust of wind swooping down from the La Sal mountains may collect both the center seeds and the ray flowers’ seeds , depositing them in a nearby piece of disturbed bare soil, establishing a new plant in the exact same way this one had been.

By Tali Hastings