Inter-kingdom Symphony

Colorado Four O’clock (Mirabilis multiflora)

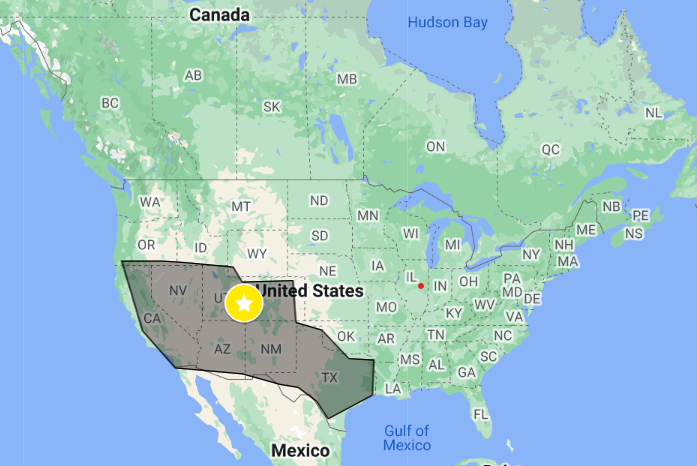

As the sun rises above Castleton Tower on the eastern border of the valley, another day is just about to begin. Seas of plants nestled on the five-acre-plot in Castle Valley, Utah are about to embrace another day of sunlight. There are a few things that are abundant in this small ecosystem—sunlight, carbon dioxide, and nutrients. Beyond the irrigation dripline laid down by Homo sapiens, water—the quintessential source of life—appears at first glance to be almost absent from the five-acre plot. That important characteristic defines the plants that thrive on 270 Pope. Each individual plant species has to have developed ways to counter the lack of water and that certainly includes the Colorado Four O’clock.

Scientists call the Colorado Four O’clock Mirabilis multiflora—characteristically named after multiple flowers blossoming on a singular root. A single Four O’Clock can have its flowers spread up to 4-6 feet wide, stemming from just one root. With the sun high over the horizon, the Four O’clock sees this as an opportunity to store as much energy as possible for the grand reveal that happens later in the evening. With petals and sepals closed, the leaves of the Four O’clock are the workhorse in the searing sun, turning carbon dioxide and water into energy. That desert sun comes as a double-edged sword: plants need sunlight to photosynthesize, however the sun also makes water evaporate more easily. The sun swipes across the horizon as the day goes by. For the Colorado Four O’clock, the day isn’t ending quite yet. Colorado Four O’clock spreads throughout the 5-acre property, soaking the last bit of sunlight, getting ready for the symphony that occurs right after dark. Soon, Castleton Tower turns from bright red to mellow pink just as stars in the sky reveal their faces. The darkness of the night provides another opportunity for the Colorado Four O’clock to shine. As photosynthesis ceases in the darkness, hormones in the Four O’clock instruct its flowers to open, in preparation for the start of the next generation.

When the darkness arrives on 270 Pope Lane, Colorado Four O’clock is running against the clock of time. The stage for an inter-kingdom symphony is set and ready to go. The bright pink flower gently opens, revealing its reproductive structures. Meanwhile, a fleet of aerial pollen dispersers are about to descend onto a field of freshly made foods. For the Colorado Four O’clock, Hawkmoths are the exclusive partners in this symphony. Colorado Four O’clock uses the energy produced during photosynthesis in the daylight to produce nectars—a sugary part of the flower that attracts pollinators like the Hawkmoth. For the flowers themselves, this is a once in a lifetime experience; these flowers will never bloom tomorrow night. The production of nectars is nothing short of rocket science; it is the only tool available to the Four O’clock to control hawkmoths’ behaviors as pollinators. Producing sugary parts like nectars is incredibly energy intensive for the four o’clock. Meanwhile, producing a larger volume of nectars does not necessarily come with more benefits to the four o’clock. As a plant with multiple flowers, large nectar volumes increase the probability for hawkmoths to visit flowers in the same plant, making self-pollination more likely, which decreases the genetic variability of the whole species. And yet, producing small amounts of nectar decreases the probability for enough hawkmoths to visit a number of the four o’clocks in order for cross pollination to occur. For the Colorado Four O’clock, getting the nectar size just right is essential to the genetic fitness of the species.

Perhaps the Colorado Four O’clock is teaching the rest of the ecosystem an important lesson—things have to be just right. The success of an ecosystem depends on a myriad of factors working in concert to ensure the checks and balances of all species. This carefully calibrated ecosystem requires everything to be perfect. Either too much or too little will wreak havoc in the system. This deliberate equilibrium results from generations of evolution. Each generation’s attempts at trying new things ultimately culminates in the magical symphony performed by forbes and moths. That inter-kingdom collaboration not only displays the interwovenness of the biological world, but perhaps the fundamental beauty of everything depending on one another to thrive.

By Jake Wang