A Moth and her flower

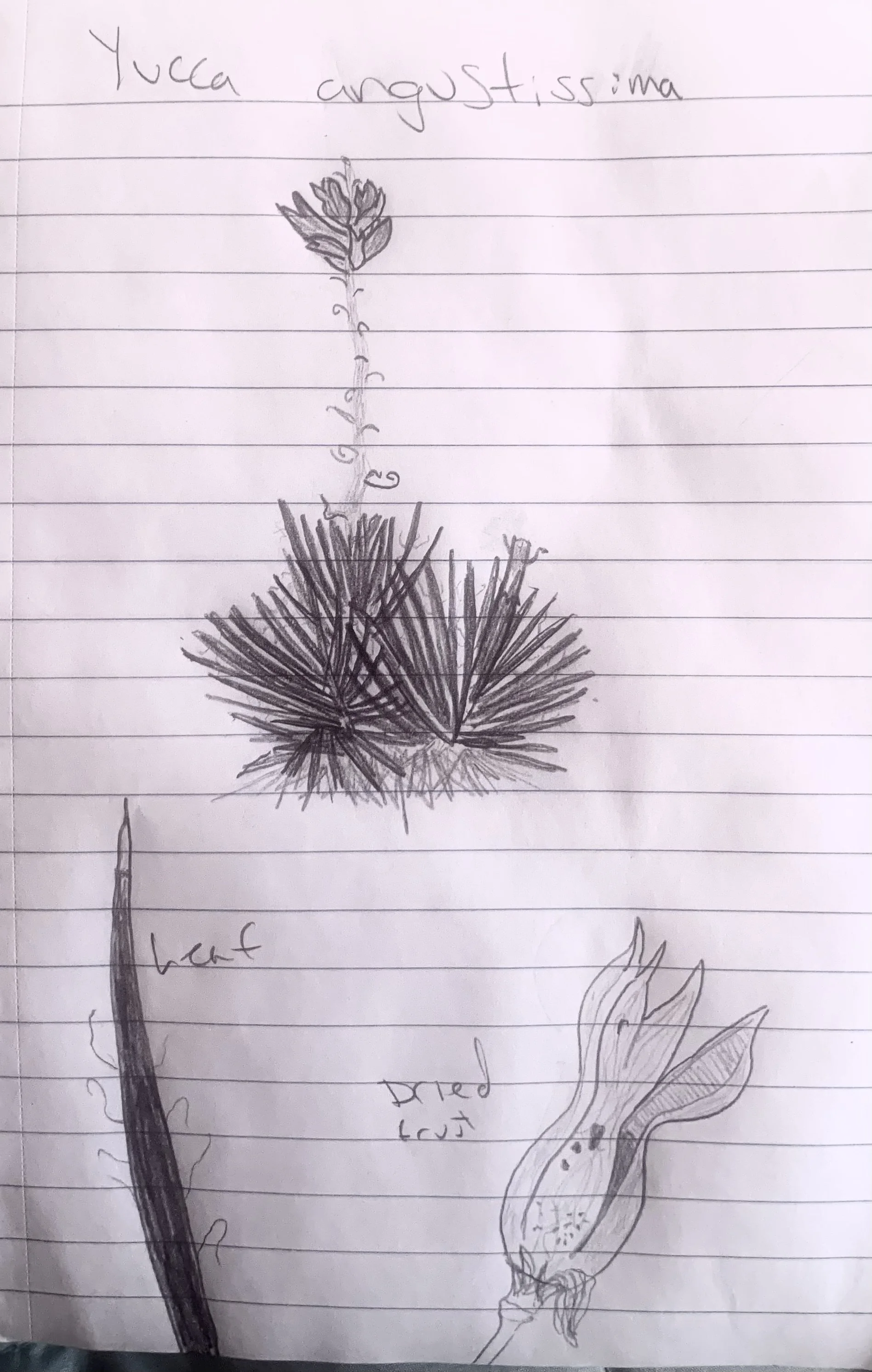

Narrowleaf Yucca (Yucca angustissima)

It is springtime in Castle Valley. Birds start to return, trees begin to replace their leaves, and the Narrowleaf Yucca unfurls its petals. A Tegeticula yuccasella moth crawls out of an underground cocoon, exposing her newly grown wings to the air for the first time. Noticing the Narrowleaf overhead is open for business, the moth sets out on her maiden voyage, her destination hanging three feet in the air. Alighting on a soft white petal, , the moth waits for a male counterpart to do the same. Mating season for the Tegeticula moth is off to a slow start.

The Tegeticula moth has mated solely in the flowers of the Narrowleaf for over thirty million years. The moth has a mutualistic relationship with this Yucca, acting as its sole pollinator. The moth and Yucca’s successful mutual relationship spread across the American Southwest, including into Castle Valley. After millions of years of peaceful existence, cows arrived in Castle Valley, decimating the Narrowleaf population. Both ranchers and cows dislike its sharp and waxy leaves. The plant’s removal and the subsequent proliferation of cheatgrass blanketing the valley in a thin but impenetrable layer of biomass for the Narrowleaf greatly reduced its numbers. As a result, Tegeticula moth habitat in the valley decreased substantially.

Finally, a male moth finds his way into the blooming Yucca, commencing the simultaneous act of moth mating and Yucca pollination. Finishing his job of fertilizing the female Tegeticula’s eggs, the male dies, leaving the female to finish the pollination job. The newly solo Tegeticula collects pollen and sticks it under her head for safe keeping. With her cargo, the Tegeticula embarks on her final voyage, searching for a new flower to lay her eggs in. For decades, this has been a difficult search. The sprawling blanket of cheatgrass successfully crowds out any Narrowleaf that wants to welcome the moth to its flower.

This time however, after a lengthy search, the Tegeticula finds a solitary three-foot stalk, alone on an island of red dirt surrounded by a barren ocean of cheatgrass. White flowers adornthe stalk, rising out of a rosette of narrow, sharp, green leaves. At last, the Tegeticula can finish her tasks. Making one last push of her wings, the Tegeticula lands on a petal, quickly walks deep into the flower, and deposits her eggs in the ovary. In her dying act, she walks back up the flower to the stigma and places the pollen carefully in the opening. The Tegeticula’s job is done.

The Narrowleaf begins to develop its seeds over the following week, while the Tegeticula eggs develop a larva inside. After a week, Tegeticula larvae hatch and begin to eat the developing seeds. The Narrowleaf is different than other species in the Yucca genus because it holds more seeds than most, and consequently can host the highest number of Tegeticula larvae. These larvae will eat 15% of the Narrowleaf’s seeds and accumulate an entire life’s worth of biomass prior to bursting out of the fruit and retreating to the ground to build their winter cocoon. The other 85% of the seeds will be dispersed by other animals, insects, and birds throughout the summer, reaping the benefits set in motion by the Tegeticula during the spring.

The work of one moth began a long chain reaction that feeds an ecosystem with the fruit of the Yucca. Before the fruit can develop, it must be pollinated. In order for the Yucca to continue its genetic legacy, it must offer its seeds to the loyal moth who pollinates it, and after the moth eats its fill, the rest of the animals in Castle Valley can come and shop at the grocery store of the Narrowleaf. These animals will soon drop a seed a distance away, beginning the process for another Narrowleaf to sprout and provide more than just one solitary stalk for the Tegeticula to land on, as the process begins all over again.

By Nat Lange