Oh Grama, Where Art Thou

Blue Grama (Bouteloua gracilis)

Midafternoon sunlight plasters the red canyon walls. It bakes the cheatgrass an iridescent gold and barrages the iron-tinted dirt blanketing 270 Pope Lane, an unassuming property resting quietly on the Castle Valley floor. Tucked behind a barn-red tool shed lies a native grass, Bouteloua gracilis or Blue Grama, standing erect and poised. Once littered with cheatgrass, like much of the grazed West, 270 Pope is now a 5-acre haven for species native to the Southwest region of North America. Blue Grama, a pioneer species, found its way to the property as soon as the invasive outlaws were removed, setting its roots in the arid soils and eventually proliferating in scattered bushes across the property.

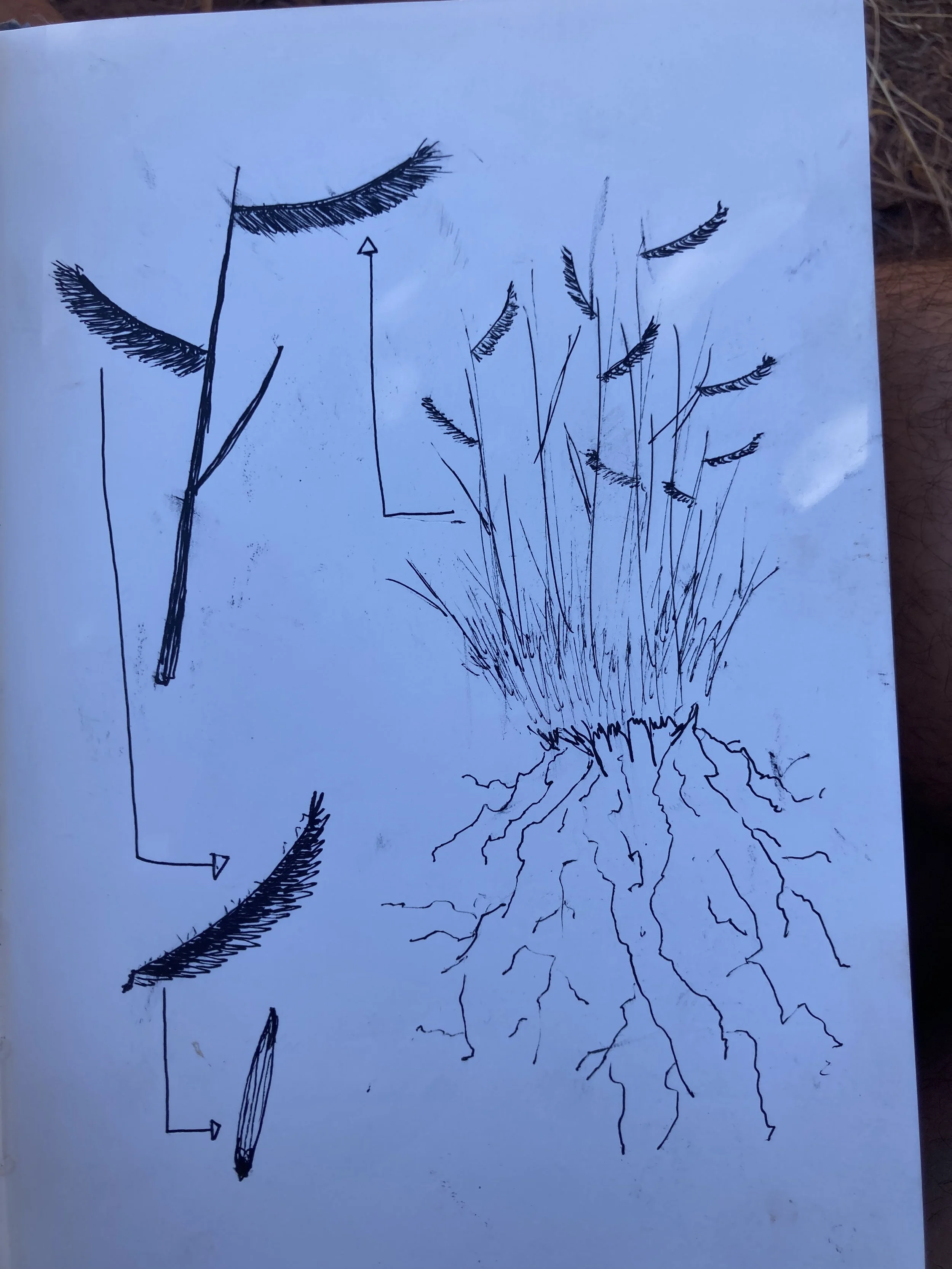

The bunches that litter 270 Pope are not grazed by cattle, and hence appear as their namesake implies, tall and graceful. Their roots are strong, fibrous, yet shallow for a perennial, residing in the top 6-18 inches of the soil. Thus, the compaction of soils by grazing herbivores in Castle Valley had been unproblematic for them. Water will rest in the very top layers of soils after large herds have compacted the soils. But despite the lack of percolation, the shallow root system of Blue Grama allows for the gathering of water, making them well adapted to the cattle grazing of the last two centuries.

However, Castle Valley is exceptionally dry, regardless of cattle presence. But, Blue Grama resists the urge to overindulge in the little liquid that rests in their arid home. Their callous roots can remain dry through long, waterless stretches, making them incredibly tolerant to the droughts that plague the valley of 270 Pope. When waters flee for prolonged periods of time, Blue Grama will enter a deep stupor, clinging on to life in a breathless dormancy, shedding exterior stems until the moisture levels of the body equilibrate with the soil. And, when rains return, they will spring back in force, unapologetic in their fullness, in vibrant greens and beet purples.

The Blue Grama on 270 Pope breathe a sigh of relief. Residing in a mostly fenced enclosure, far from prying cattle, they are unfazed by the prospect of grazing. While very well adapted to the soils compacted by grazing cattle herds, Blue grama do not thrive under such conditions. Overgrazing from cattle will leave them unimaginably stout, stripping them of the grace after which they were named.

Ungrazed, Blue Grama will build beautiful homes, starting from a single stem and expanding cyclically through tillers, rhizomatous or above ground. As they continue to clone outwards, the initial stems will fade into a quiet death, resulting in a grassy periphery ring, hugging the exposed dirt left in the wake of the brittle elder stems. And, as if its graceful stiffness and homebuilding prowess weren’t enough, they produce a wildly decorative flower head (for a grass, that is), comb-like and purple, due to horizontal alignment of seeds along one side of each spike. Once mature, each spike will curl upwards, revealing its purple underbelly, and spreading the teeth of its comb to reveal pollen-containing anthers, releasing their pollen to winds.

In late summer, the Blue grama nears the end of its growing season. It’s late September and they will grow until the first winter frosts which can engulf the valley in a month’s time. They have been photosynthesizing for a mere 40-50 days this year, since late spring, when the cool temperatures receded and the soils exposed themselves to the warm rays of sunlight, reflecting off the stone monolith, visible from the heights of their flowering heads, standing erect and graceful, mimicking the posture of the Blue Grama’s desire. They are finally reaching maturity, dispersing their seeds, beginning the upward curl of their seed stalks, and losing their rich colors. It will be many months before they begin their regrowth, but on 270 Pope they will be safe, free from cattle grazing, and nurtured.

By Jonah Rosen-Bloom