The Tea of Hope

Mormon Tea (Ephedra viridis)

Southeast of the chocolate, muddied waters and nestled in a red rock cradle, resides a thriving ecosystem. This ecosystem of flora and fauna dwells at 270 Pope Lane in Castle Valley, Utah. The southwestern sun illuminates the sides of the rocky crib, casting light from the tops of the canyon walls, down to the Juniper trees that lay midway down, slowly illuminating the entire space as the day approaches noon. On the valley floor, the 270 Pope residents welcome the light after a dewy dawn.

On a flat rock slab, the Western Whiptail soaks up the sweltering midday sun. On sensing the contrasting shadow of an approaching footstep, the desert lizard darts away in a flash. On a diagonal pathway from the driveway to the back side of the house, the Pinyon Jay flaps to a tall garden pole, and perches atop it, remaining still as if a statue. At first a black buzzing ink splot, then clearer as it approaches, the Montana Beetle clumsily hovers, then lands on my toe. This sets the fauna scene as I sit in the presence of the mighty, stoic Mormon Tea shrub, wondering about its duties as a floral resident of 270 Pope.

With my colored pencils in hand, I sketch the Mormon Tea as questions swirl in my mind. How did this craggy claw-like spray of a plant get here? Did Mormons really use it to make tea? Why does it so closely resemble horsetail, a plant I associate with wetlands, the opposite climate and setting? Luckily, I have the tools to answer these questions.

Sitting with the Mormon Tea, my companionable shrub, I flip through several horticulture books, settled in the shade of the large Sand Sagebrush and next to the Broom Snakeweed. A strong gust of wind shoots through the red rock cradle, disrupting the upright nature of the dry, desert flora. The plants lean with the wind, seemingly defeated by the gale force—all but the Mormon Tea, which stands stout and solid.

This sturdy shrub stands no more than four feet tall and is almost spherical in appearance, like a huge, skeletal yoga ball. Its gnarled woody trunk diverges into several thick woody stems that branch outward and then upward. But this skeleton seems invisible, as its clusters of rigid upward-facing, green needles encase it, creating the spherical shell. With a closer look, one notices that the needles are jointed, a new set of two symmetrical ones sprouting from the original joint.

If it were not for the current human residents planting these few Mormon Tea shrubs here, the plant would have likely populated itself via wind pollination, perhaps on a gusty day such as this. Ephedra viridis, or Mormon Tea, is one of 40 species within the genus Ephedra. This plant is “large-seeded” and the seeds spread by wind. Besides wind propagation, the sprightly kangaroo rat, indigenous to the region, also contributes to the growth of Mormon Tea populations by caching large seeds to later disperse throughout the land.

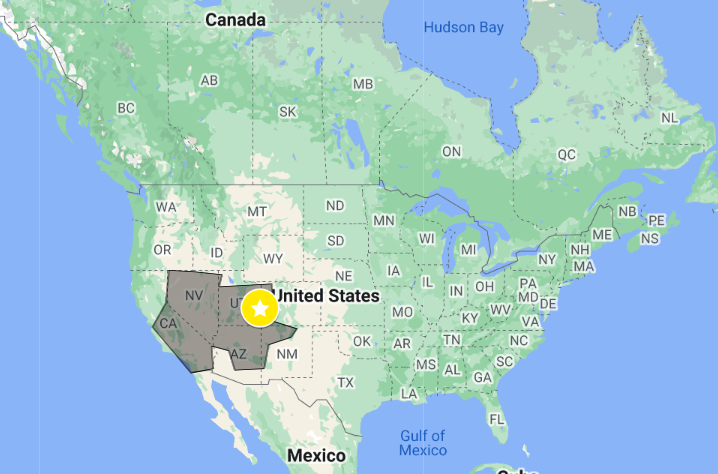

It would be a happy day were that kangaroo rat to scatter some seeds. Mormon Tea is native to the American Southwest after all, and serves essential ecological roles. For example, as the West has become drier and warmer with climate change, the land has experienced dramatic weather fluctuations with hotter hots and colder colds. As a product of these changes, the land has been altered—more flooding, more erosion. Mormon Tea serves as a staple in the land that sends roots down to secure loose sediment and prevent it from crumbling and creating further erosion. But as things erode, they also evolve. Mormon Tea can say this of itself.

Mormon Tea evolved to be able to photosynthesize in a way that fit its anatomy. While most plants intake carbon dioxide and sunlight through their leaves to fuel themselves, this woody shrub adapted to absorb carbon dioxide and sunlight via tiny scales on its needles. Even more than purely intaking energy for survival, Mormon Tea has learned how to undergo “secondary growth ,” a process by which the needle’s girth increases, making the plant much more likely to survive wildfires, a common process in the West. Finally, Mormon Tea has also outsmarted part of the threat of browsing that western plants face. By producing toxic tannins, Mormon Tea poisons livestock that choose to nibble its needles, making it a more resilient plant likely to survive.

In the 270 Pope community, Mormon Tea represents resilience. It demonstrates steadfastness. It suggests hope. Mormon Tea stands solid and sturdy, not easily taken down. While the West undergoes change, surely so does Mormon Tea. But while it sometimes appears that our surroundings are only eroding and breaking down, in the natural world they are also evolving and building up. So may I suggest, go steep yourself a bunch of needles, and have a sip of some of the tea of hope, Mormon Tea.

By Katie Spegar