Sketching Snakeweed

Gutierrezia sarothrae – Broom Snakeweed

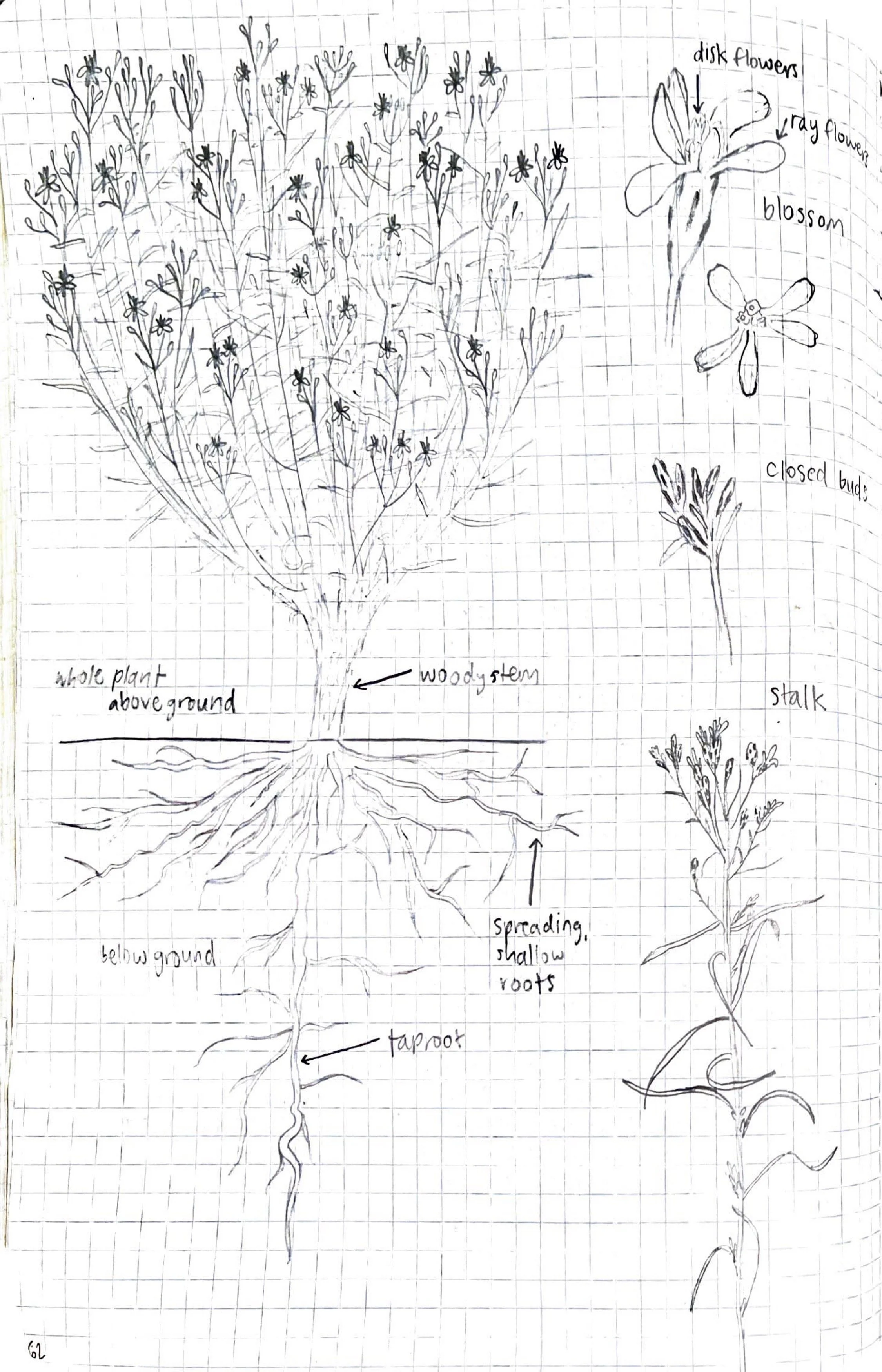

My knees tucked into my chest, I sit curled under a bushy sagebrush to find refuge in the snippet of shade shared by the bush’s soft green leaves. I sketch the small yellow blossoms of Gutierrezia sarothrae, broom snakeweed. They grow in clusters atop the green stalks branching off the shrub’s woody base, barely bigger than my pencil eraser and matching its bright golden color. Each bloom has tiny round disc flowers with the plant’s male stamens and female pistil poking up out of a ring of oval ray flowers, bright yellow color drawing insect pollinators that linger nearby. Most of the petal-like ray flowers have unfurled on the plant I’m drawing, creating a sunny mosaic of blooms and buds. Layers of tiny green bracts that look like scales connect each blossom to their stems. These bracts, along with the composite flowers made of numerous, individual ray and/or disc flowers, make broom snakeweed a member of the Asteraceae or sunflower family.

The broom snakeweed plants spent this summer soaking in the sun, growing into round yellow domes about a foot tall. The plants look small compared to the plants they neighbor, intertwining with stalks of Indian ricegrass, sprawling Colorado four o’clock, and fronds of sagebrush. Broom snakeweed nestles into distinct communities of plants throughout the West, growing in a variety of ecosystems. In sagebrush-strewn intermountain desert regions, like Castle Valley, broom snakeweed accompanies shadscale, black sagebrush, sand dropseed,, and gramas. The same plant might grow alongside big sagebrush, rabbitbrush, and downy chess on foothills and in juniper-pinyon forests, or with mesquite and soapweed in Southwestern oak forests and lower ranges.

I burrowed a shovel into the rust-red soil in the yard, digging up one of the many broom snakeweed plants to peek at its roots. One main taproot extends downward, with a halo of smaller periphery roots holding on to clumps of soil. The taproot reaches down to draw in water, extending as far as two feet deep, while the smaller roots anchor the woody stem. The dual root system provides an advantage over grasses’ shallow roots, allowing broom snakeweed to take up moisture before it’s sucked away by other plants. Sketching the roots, I move to the long, thin leaves twisting out from the stem in every direction. Each leaf has miniscule pores, called stomata, that draw up moisture and transpire. Seeking water despite the arid soil, they strive to quench the plant’s thirst during the summer but can drop off if drought becomes intolerable. Without leaves, broom snakeweed can still photosynthesize through their green stems, adapted to the baking sun of the West.

The plants sprouted in early spring, jumping at the invitation to root in the red soil when the two people who live at 270 Pope cleared cheatgrass away from parts of their yard to let native plants establish. In other areas of the West, broom snakeweed sprouts after fires, heavy grazing, or road construction, seizing the opportunity to spread without competition from grasses, sagebrush, or rabbitbrush.

The plants were dormant seeds lying in the soil at 270 Pope, buried under a layer of cheatgrass duff. Though the seeds were mature after 6 months, they waited – perhaps for years – for a disturbance, to reach the light they need to germinate and poke up through the soil. The seeds also sought moderate temperatures, waiting for 59- to 86-degree weather to start to grow.

The winter wind that blew seeds to 270 Pope spreads broom snakeweed throughout its range across western North America, from Alberta in Canada to Texas. Without wings or insect carriers to direct the spread of seeds, broom snakeweed flies on gusts of wind for dispersal and often grows in clustered groups. Though the seeds hope to land on well drained, limestone clay loam, broom snakeweed can tolerate a variety of soils – sandy, shallow, rocky, or gravelly, if the soil is well drained. Here at 270 Pope Lane, broom snakeweed found brick red river-deposited sediment, matching the warm glow of Castleton Tower.

My pencil sketch doesn’t capture the vibrant yellow and green of broom snakeweed, standing out against the rust-colored soil and brilliant blue sky. Though they’ll die back in the winter, these plants scattered around 270 Pope will cling to some of their sunny color as they dry out and linger in the cold, growing again when spring comes to Castle Valley. As I stand up from my patch of sagebrush shade, shaking the pins and needles from my legs, I walk across 270 Pope to encounter broom snakeweed plants scattered all over the plot. They’ll grow for four to seven years, reaching up to a yard high – tall enough, perhaps, to cast a shadow for me to crouch under as I sketch a new resident of 270 Pope Lane.

By Ellen Haney