“I forgot to bring my death maps,” said Mike. An off-hand comment, as if a map marking is dead humans is a normal thing to leave on the kitchen counter. Mike Wilson is a human rights activist and is Tohono O’odham, living on tribal land. He emulates a warm father-like energy--dad humor mixed with a dose of realism. He is the type of guy to give you the shirt off his back, regardless of the blue pen stain on his breast pocket. His land, a home from time immemorial, has been disrupted, and splintered by the U.S.-Mexico border wall.

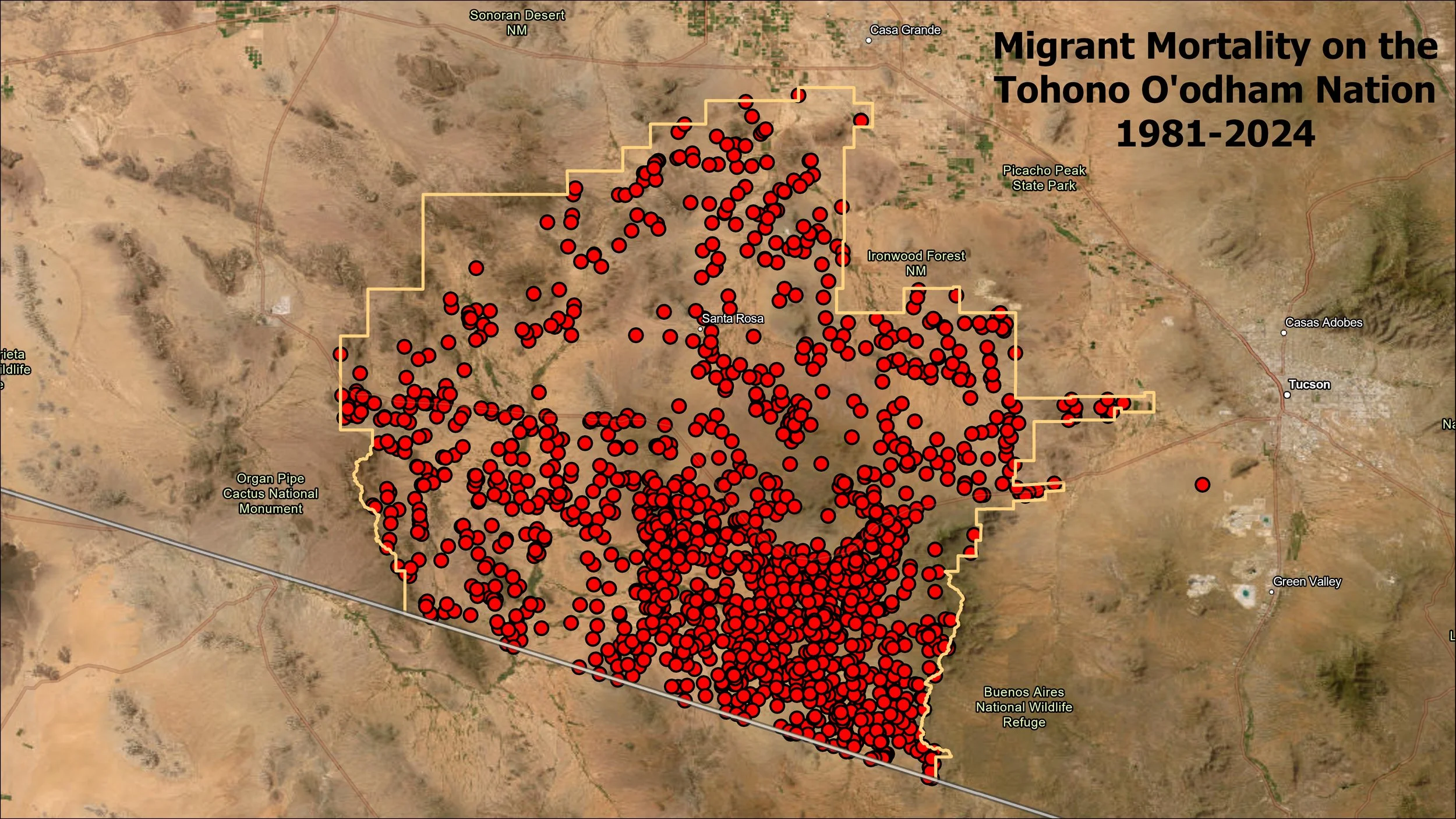

The Humane Borders death map confronts and quantifies the incomprehensible amount of deaths along the border. Each red dot on this map denotes a body, a life, a story. Mike witnessed migrants passing through the Baboquivari Valley, dying on tribal land by the hundreds. He estimates over half of all migrant deaths in the Tuscon area, occur on tribal land. For twelve years, he provided life-preserving aid, by putting out water for migrants. He maintained a water cache, a strategically placed water supply. His actions caught the attention of his tribal council and the Border Patrol. Mike faced fierce opposition and intimidation from both groups, reasoning that his water would encourage more migrants to come. Mike is a true hero. His life and actions should be celebrated, but instead are despised.

A few hundred miles west of Mike's water caches, a different journey begins. The Pacific Crest Trail is a long-distance hike from Mexico to Canada, starting at the US-Mexico border. The scorching sun settles on a wall of steel slats, heat waves slipping through the gaps. Hikers stick an arm or leg through the wall’s towering bollards, then head north. Thru-hiking is an adventure of endurance and privilege. For undocumented migrants, the journey north is one of necessity and survival.

It’s in The United States government's best interest to dehumanize migrants. Aiming to decrease unauthorized crossings, in 1994 the US Border Patrol implemented the Prevention Through Deterrence (PTD) policy. Making the journey more hazardous, they Militarized border towns and pushed migrants to endure more dangerous routes, like the Sonoran desert. The U.S. government knew the consequences; they knew it would increase migrant deaths. Temperatures reaching 120 degrees, beat down on the rugged landscape, and on those attempting to cross it. Since implementing the policy, the government has reported over 10,000 deaths. Many remains are never recovered, The true total is much higher.

Traversing the valleys in the Tohono O’odham’s sacred Baboquivari Mountains, Mike points his Dodge pickup towards Highway 86 to refill his water caches. His tank labeled “Agua” sloshes on the dirt road, dancing with the potholes. He steps out of his truck, it’s dust-caked and battered from a decade's worth of weekly trips.

He unloads clear water jugs and positions them to form a cross, a sign of hope for migrants. Mike is a lifeline in the desert, like a river replenishing hope, where it runs dry. In the blistering afternoon heat of the Southern California Desert, I walk north on the Pacific Crest Trail. Barrel Cacti, Cholla, and Creosote fill the slopes. Faced with a bout of food poisoning, I needed water: the nearest reliable source, a day’s hike in either direction. My stomach was a washing machine, running with the lid open. Tumbling towards the Highway 78 underpass, I was satiated in its shade. Shade is not the only offering here. Under the support beam of the underpass, is a water cache. Gallons of water for hikers, neatly arranged, often replenished. Relief, renewal, and rejuvenation ooze from the liquid life. This water is not here by luck. A group of eclectic volunteers, resupply this cache. Known in the hiking community as trail angels, they are celebrated as such.

Photo from Human Rights Watch

Mike and others providing humanitarian aid are considered enemies of the state. “My tribe was going to label me a domestic terrorist as if my water was a weapon of mass destruction.” Since when do terrorists work to preserve human life? Despite his resilient efforts, he isn’t labeled an “angel”.

Aid groups have been fined and prosecuted for engaging in humanitarian work. Volunteers for the activist group No Mas Muertes were putting out water in the Buenos Aries National Wildlife Refuge when they were charged with “dumping of waste”. Other volunteers have faced fines for “abandonment of property” This is retaliation against humanitarian aid, exposing the government’s priorities. Human life and compassion come second to ruthless border enforcement on federal lands, while trail angels on the PCT—also on federal lands—face no such consequences.

Mike drove every Sunday, for 624 weekends, with a truck full of water to his water caches. This time, he arrived to find the gallons placed meticulously the week prior, had been cut. One hundred desert life preservers, destroyed as if they were bombs. Mike said, “Here is a history of border patrol agents in the field destroying water barrels… I had those slashed by the hundreds.” A universal experience for aid groups. A human rights violation by the United States.

When trail angels assist strangers attempting a difficult, but chosen journey, they receive love. When aid groups assist strangers migrating for their lives, they are criminalized. Hiking and forced migration do not have the same consequences, the action of putting water out is the same, but the reaction is different. Border aid groups are treated unjustly for providing basic survival needs. Where policy and society want to create divisions, our humanity seeks commonalities. Mike Wilson is a border angel.