In the shifting shade of an orchard in the afternoon light, children dart like birds through the trees, vanishing and reappearing between withered trunks. Amber light sparkles through the gnarled branches, pooling in the soft spots along the flowering wild grasses, beaded with dew. Apples lie scattered at the base of the winding roots, bruised and bitten. A boy runs through hollow tunnels, bent and carved by deer padding through the bushes. He yells and laughs before he notices his friends have disappeared behind the walls of shrub. He crouches, before laying on his belly to hide. With the boy’s chin in the dirt, he stares at the thick blades of grass–the worms and isopods inching through the soil, exploring small forests. Mesmerized by the miniature scale of the world in front of him, he pauses, before looking up at the cover of the trees spreading earth across the sky.

That boy was me. I played in orchards as a kid, where the trees felt like cathedrals. I never thought about the apples or where they came from, because they felt permanent. Like they had always been there: as timeless as the dirt under my nails, and just as irreplaceable as the stars. It wasn’t until I spoke to an older man that I began to understand how fragile those trees really were, and what depth of history they carried with them. That history began long before I was born.

In the early days of North American orchards, apple trees flourished across homesteads, farms, and small towns. Each tree fruited unique flavors, colors, shapes, and blemishes, cultivated for their specific uses—cider, baking, fresh eating, and show. But as industrial agriculture rose in popularity, monoculture took over, and many of those trees were torn up. Ripped from the earth, to make way for standardized orchards, in neat rows. Many, forgotten and abandoned. I don’t blame them. The market demanded it. Names like Polly Sweet, Summer Ladyfinger, and White Horse disappeared, either into obscurity, or extinction.

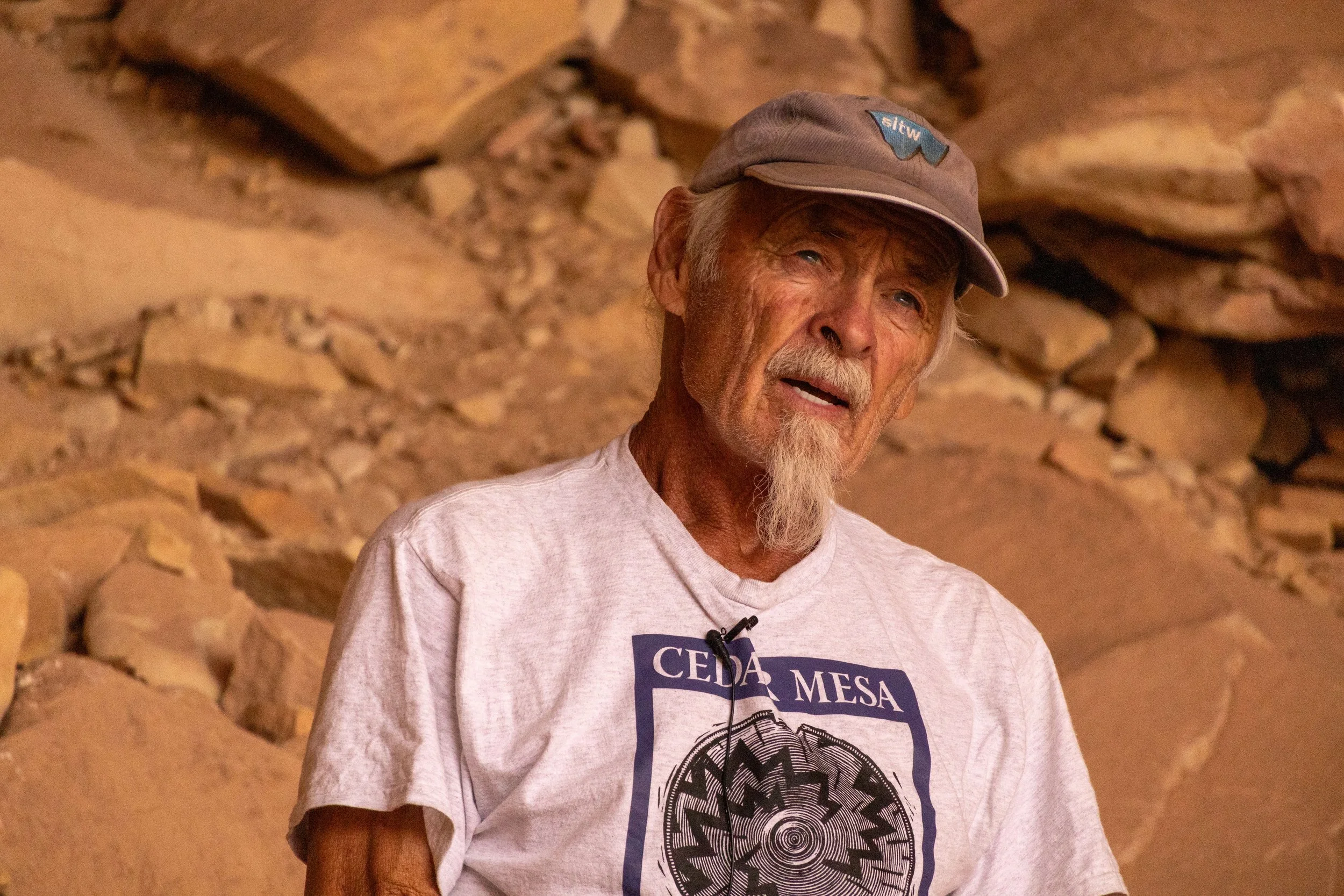

In the hills of Montezuma County in Southwest Colorado, Jude Schuenemeyer greeted our group on a chilly day. With a patterned collar shirt and a Nature Conservancy hat, he twisted the small ring on his left hand. His soft eyes passed over us, looking up at the heirloom tree that dangled apples as green as the leaves, hanging at nose level.

“So here's something you guys have to know about apples,” he said, crouching under the tree. He pulled a short-bladed knife from his hip and reached into the branches, twisting off a twig. “Apples are not true to type from seeds. Without human interaction, all of the cultivars that exist will go extinct.” He sliced into the branch, splitting the ends apart into a V. “There were 20,000 cultivars a hundred years ago, and we're down to about 6,000 cultivars now, which means we lost about 14,000 varieties of apples.” He paused. “We lost a lot. We lost an enormous amount of cultivar diversity in how those apples were used and what they represented to people.”

That scale is hard to grasp, until you consider what remains today. Walk through your local grocery store, and you’ll likely find only a handful of varieties–maybe ten, at most. Every apple you see has been engineered, not for individuality, but for uniformity and convenience. In many ways, this has been a success. Engineered apples are designed to thrive in large-scale agricultural systems, with higher yields. Traits like a resistance to bruising and longer shelf lives allow them to be transported long distances, to feed larger populations. For consumers, predictability in color, taste, and shape caters to busy lifestyles and allows them to be more accessible and available year-round. In a world of billions, modifying and mass-producing apples became essential, in order to keep shelves stocked.

Yet, while grocery store apples meet the demands of a fast-paced world, something irreplaceable has been left behind. Orchards with staggering variety preserved much more than just fruit. They preserved the richness of choice. Choice which connects us to our food with a much more personal connection. Diversity may well have been a luxury, but it was also resilience, culture, and creativity, nurtured by generations of farmers and apple cultivators. Each apple on a tree was a symbol of their identity, and the community that surrounds them. In the pursuit of perfection, we sacrificed that diversity, erasing a living library of flavors that once enriched our lives.

But not everything was lost. Thanks to a centuries-old technique, rare apple genetics endure.

Jude sliced off another branch from the tree above him. “To keep these things going, we graft.” He pointed at the base, buried by muddy leaves. “You see this scar across here? That's the graft line. This is the work of somebody from over a century ago.” Indeed, a faint line was visible on the bark: a trunk Frankensteined together, like patchwork. I thought about the trees I used to play around. Did they have graft marks?

With technique and precision, you could sustain a variety solely on another tree. Or, you could fuse two desirable traits into a single tree. Maybe, say, grafting a Ruby Red onto a Red June. By hand, you could combine the hardiness and adaptability of one with a uniquely sweet flavor of another, creating a new variety entirely.

He leaned forward. “I think of grafting as one of the greatest leaps of human imagination. To understand it, there was a tremendous, tremendous leap of human imagination. I put it up there with the invention of the sewing needle.” He smiled, in a deja-vu kind of way, like it’s something he’s said many times before: as if his awe still hasn’t faded.

Jude rotated the branch in his hands and held it up for us to see. “If you have an apple that you really like, and you plant those apple seeds, you're going to get something very different from what you originally had.” In that sense, apples are quite different from other crops–they resist being shelved or frozen in a vault. Apple varieties will vanish if left to nature alone, it’s as simple as that. Each type is tied to us, dependent on human hands to keep the genetics alive. By tending to them, orchardists like Jude allow future generations to taste what we once savored, and to spit out the same seeds. As Jude said, “People and apples are very much alike.” Rather than being locked away, they need to be alive, rooted in the soil, and cared for, as though they, too, crave a hand to turn their branches and remind the world that they are still here. And so those orchards may provide that shade, one day, to those kids who ran around them and climbed across those gnarled limbs.