The Violet Warrior

Hoary Tansyaster (Dieteria canescens)

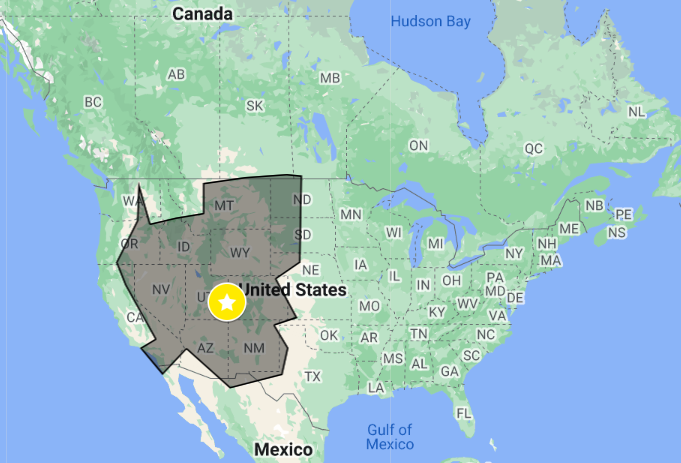

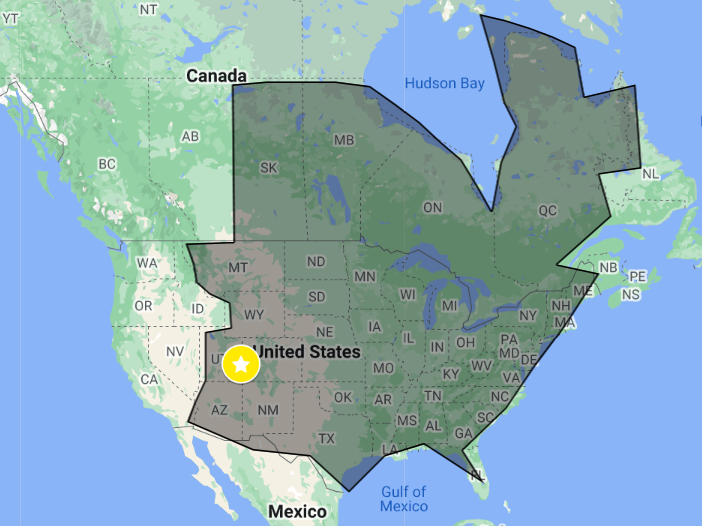

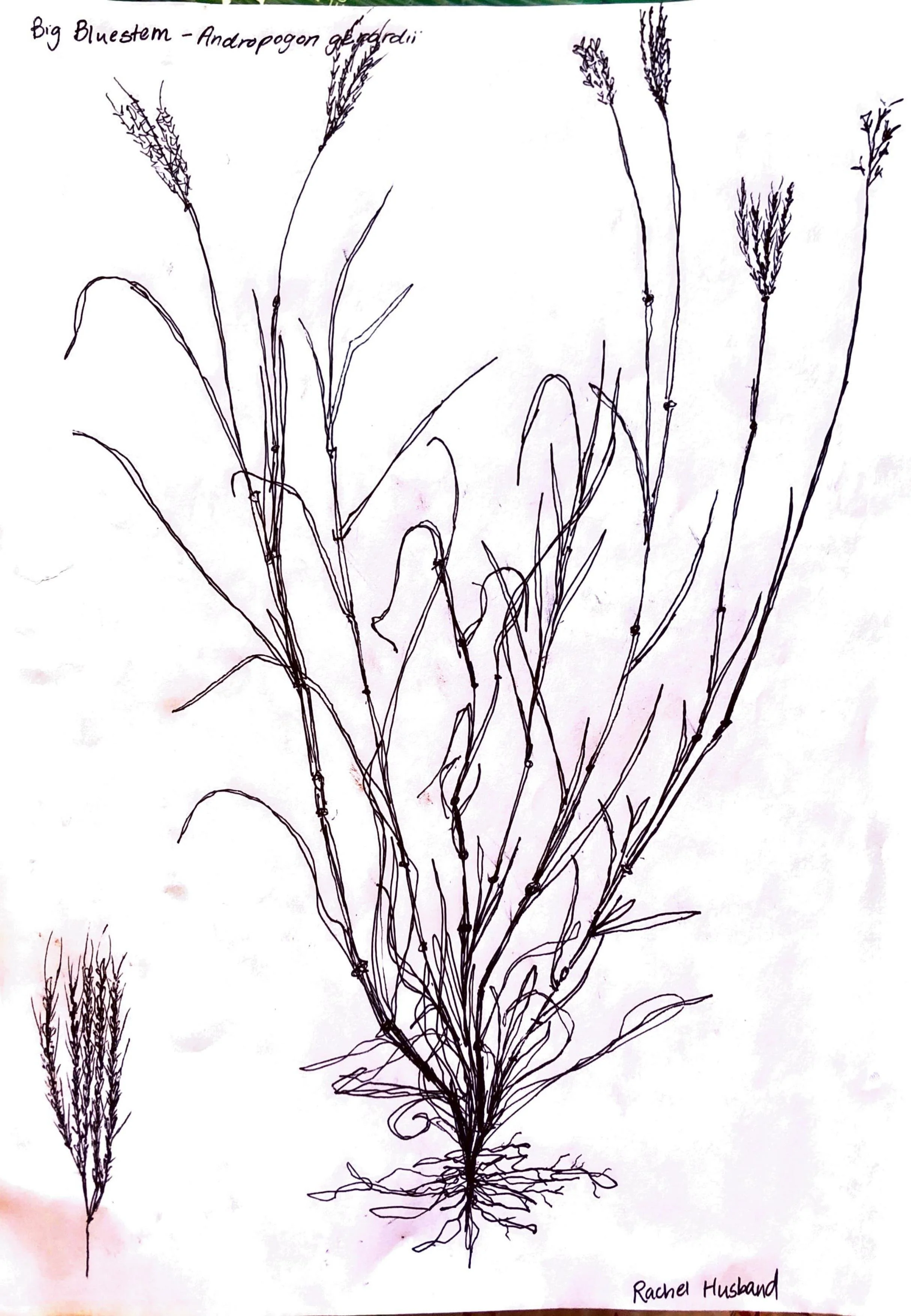

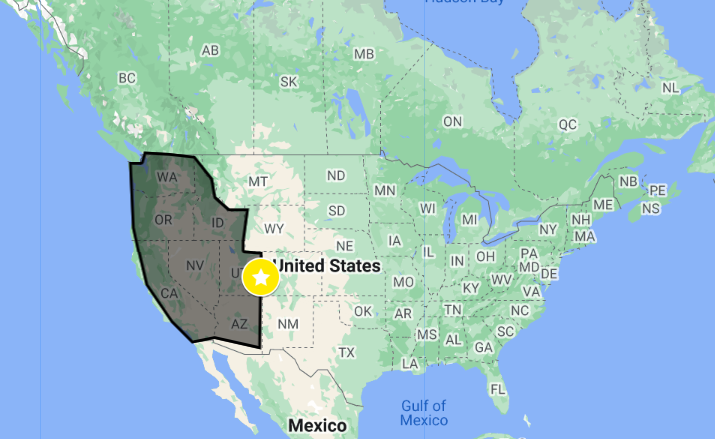

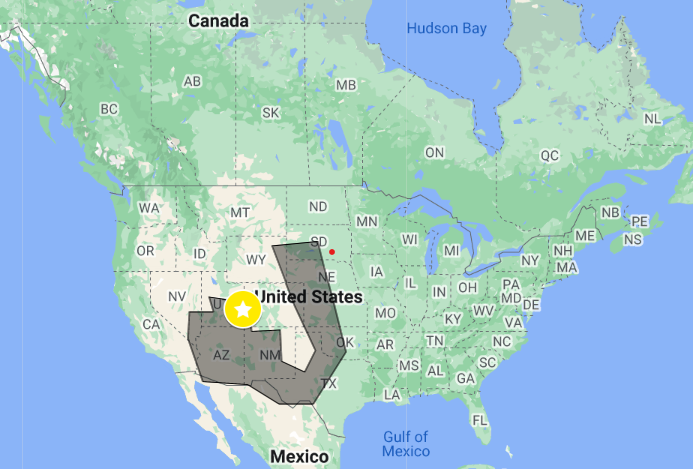

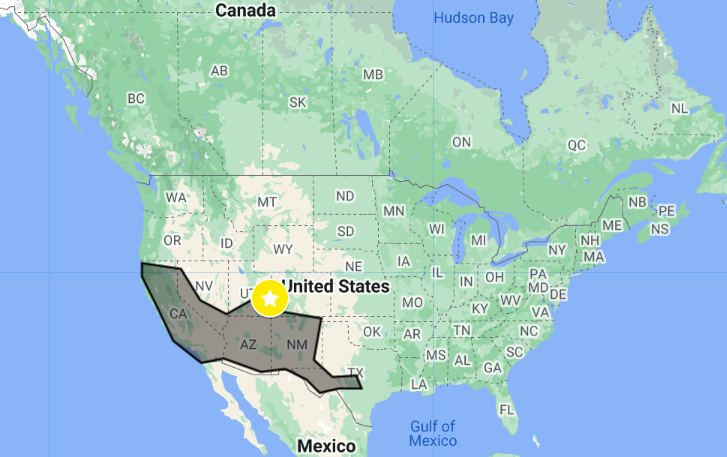

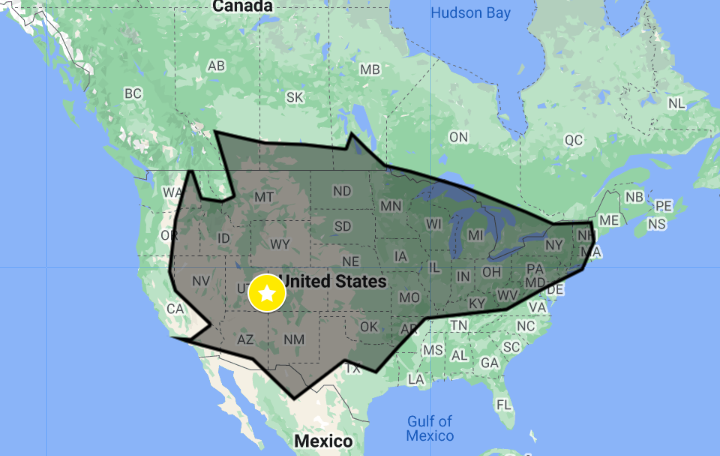

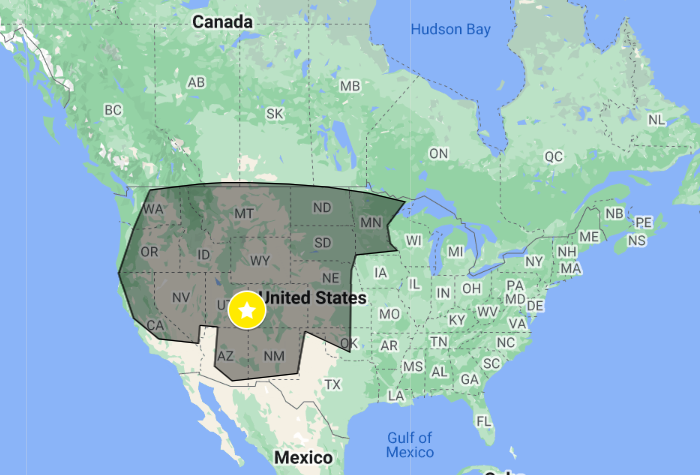

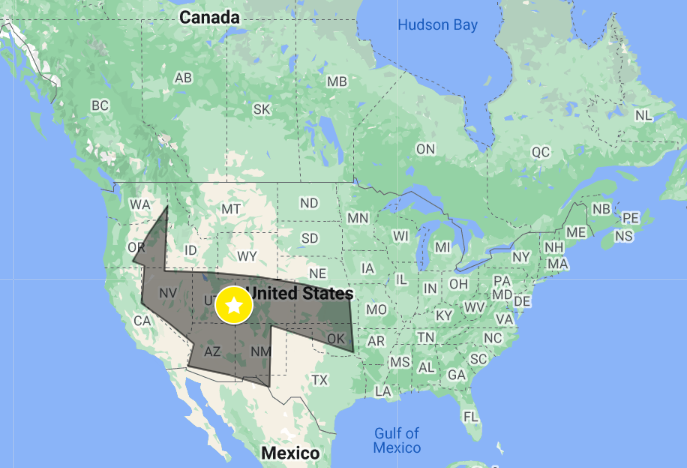

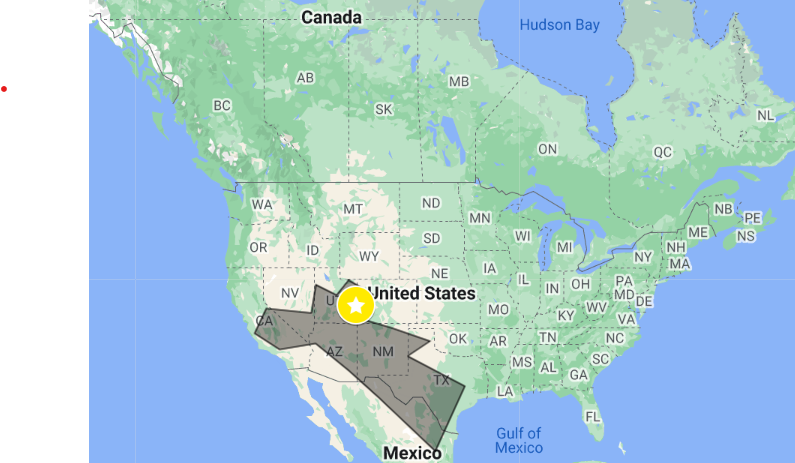

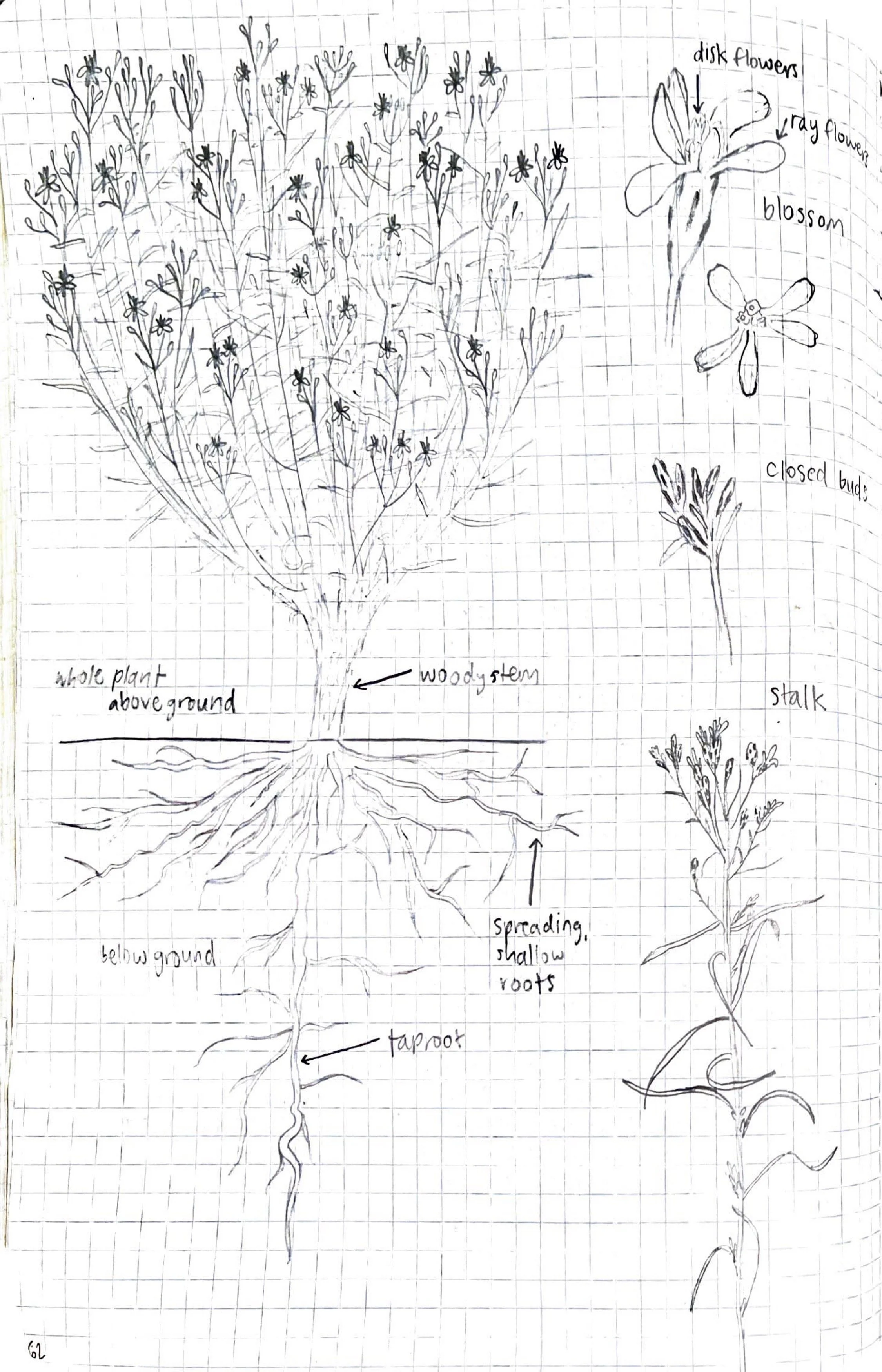

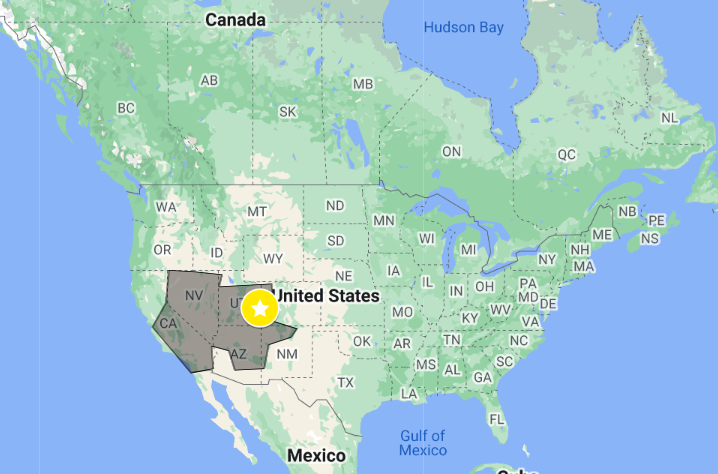

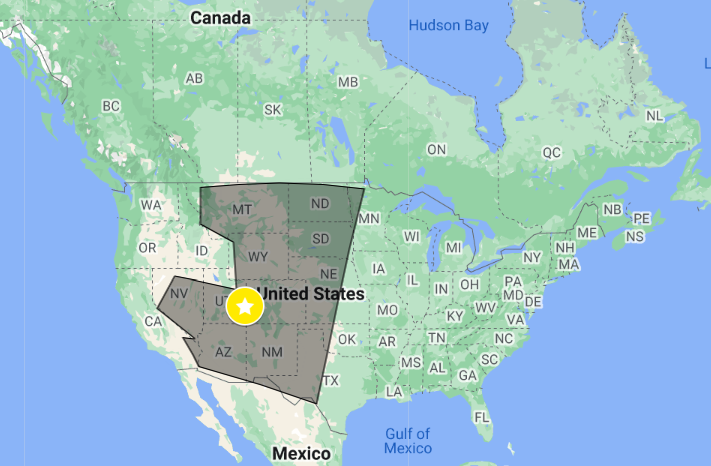

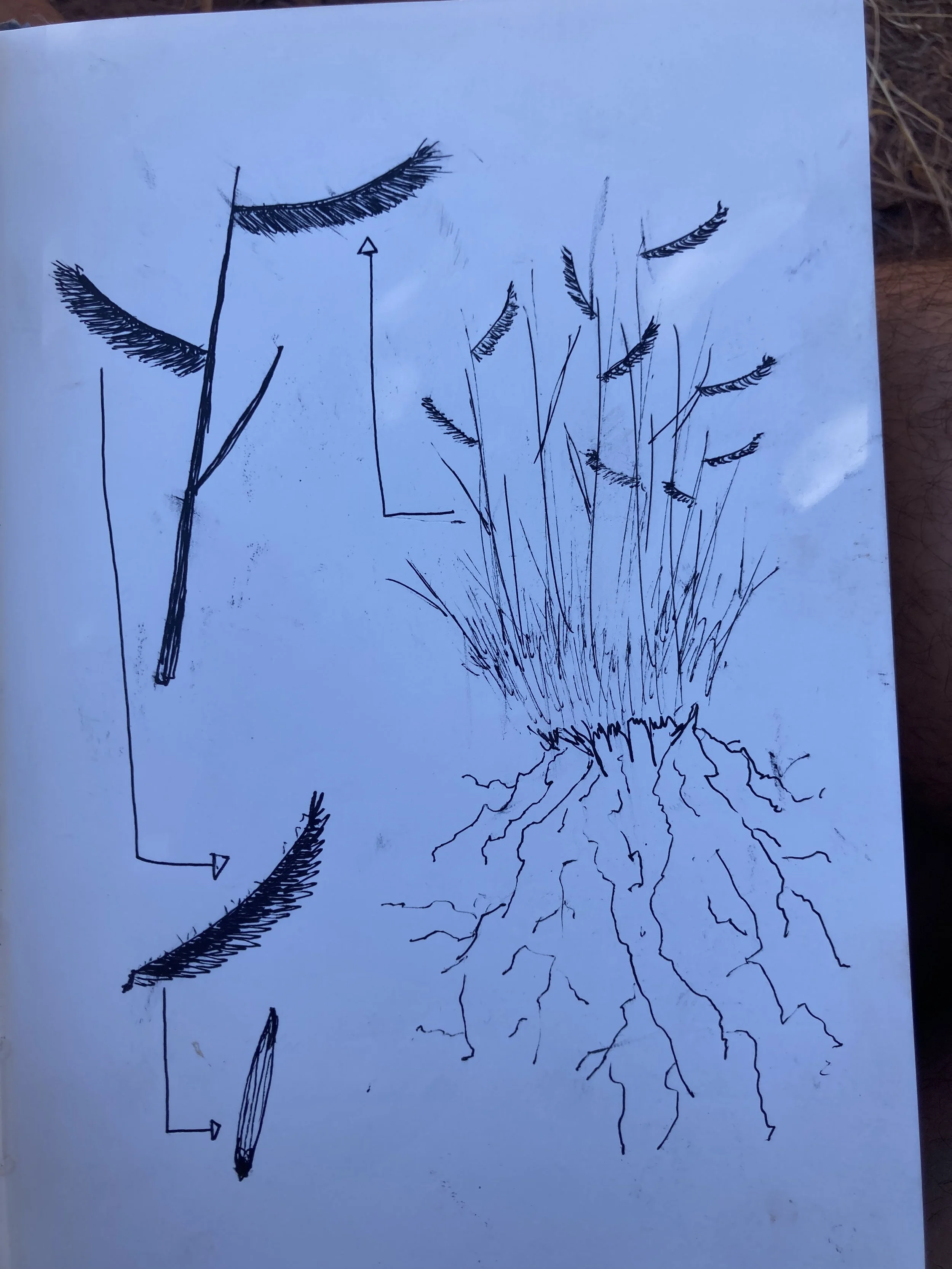

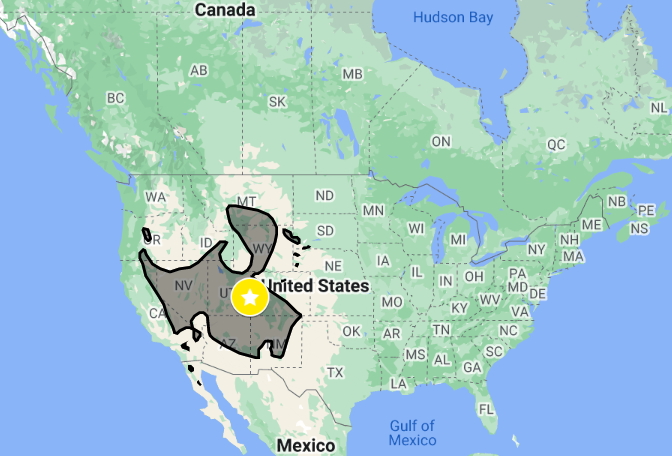

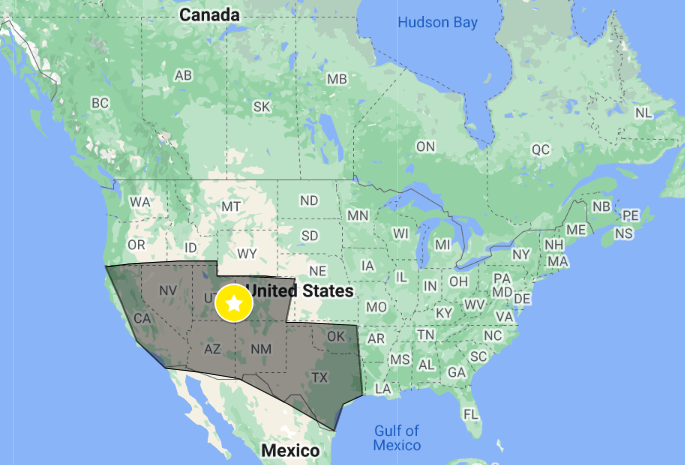

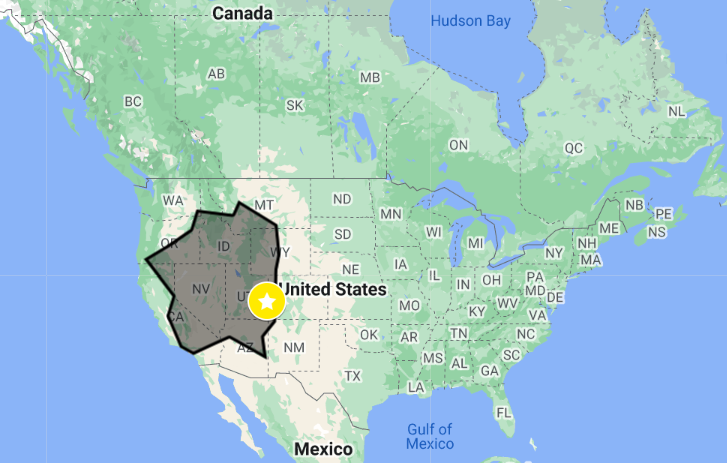

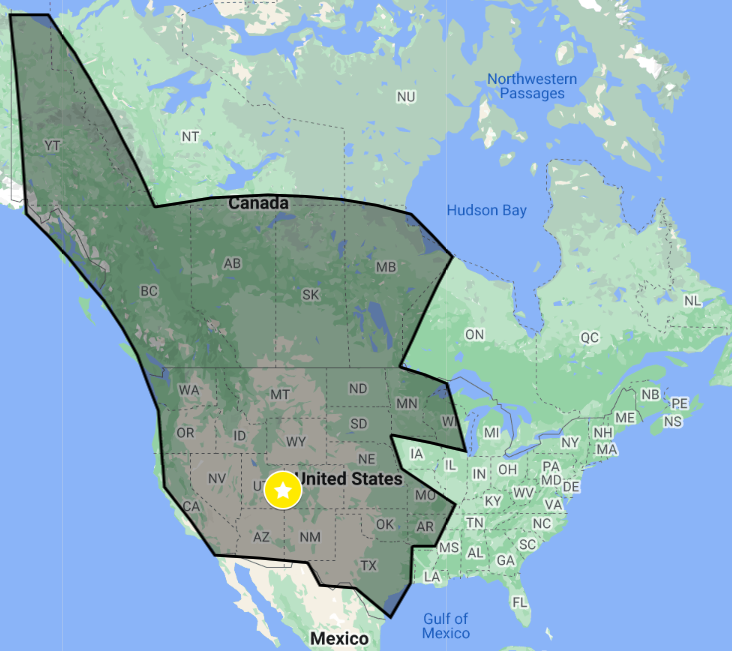

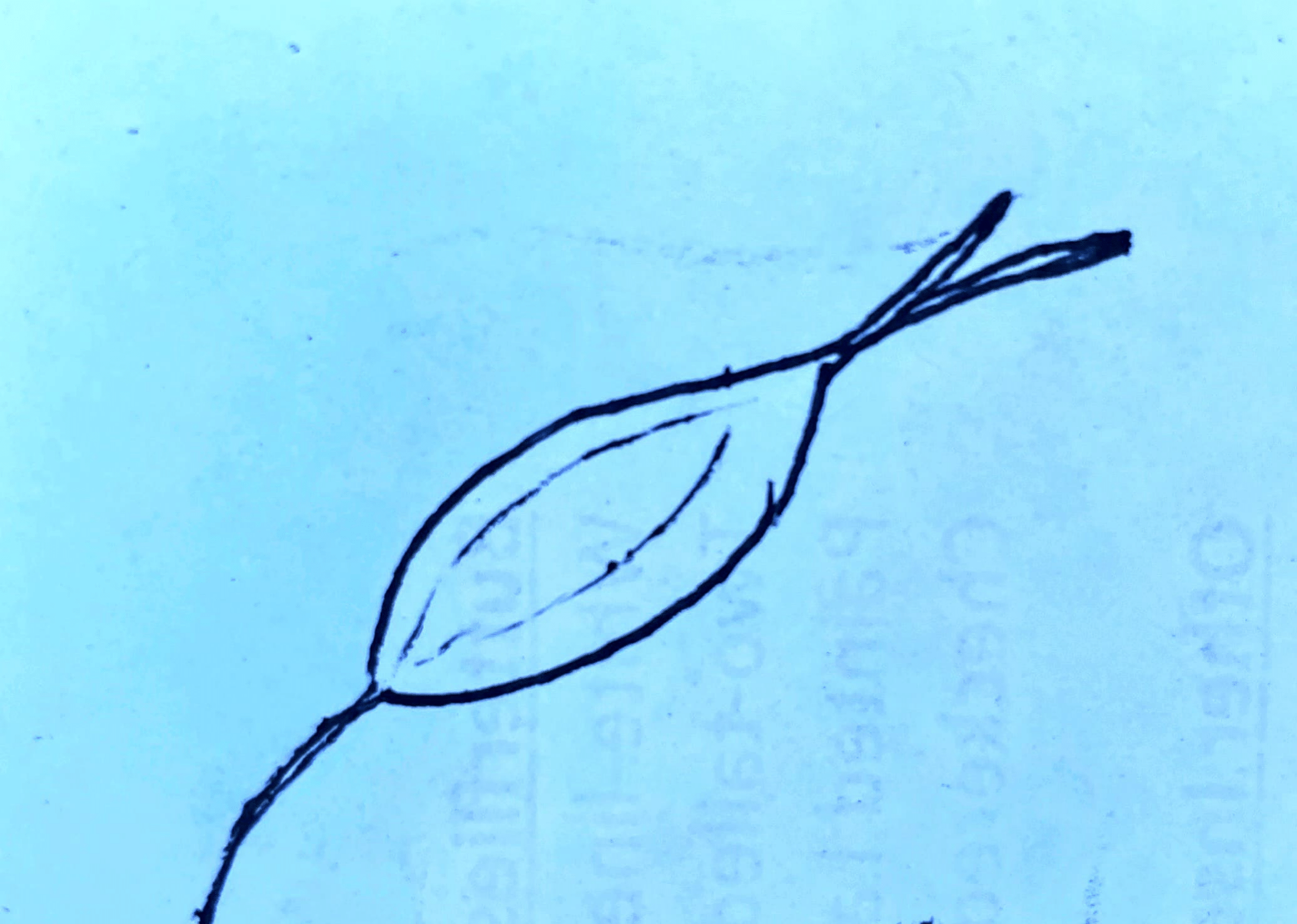

First to rise out of a scorched earth and last to fall victim to the relentless grazing of cattle, the Dieteria canescens, previously known as the Machaeranthera canescens, and commonly known as the purple aster, seems to be the cockroach of the daisy family. It has survived the hundreds of years of grazing that decimated countless other species and has stubbornly managed to hold on to its native roots that extend throughout western and central North America. Its violet hue evokes a sense of royalty that contrasts its scrappy, resilient nature. A plant that is always thinking of its next move, its seeds are quick to mature and are spread easily. Its life is short, no more than a year, but that is plenty of time for it to extend its purple flowers up toward the sun, blooming at the tail end of summer, just as the first cool breeze starts to float through. It harnesses the wind to spread its offspring throughout the desert in late autumn, only four to five weeks after flowering. In that time, it not only sustains itself, but provides habitat and resources for its native community of small mammals and birds. Sage-grouse rely on the insects who reside in the purple aster during brood rearing season. The vibrant purple flowers are frequented by sweat bees, green sweat bees, European honey bees, bee flies, and cabbage white butterflies. The aster is stubborn and persisting, emerging out of the ground to make a home for others even on the most desolate landscapes.

Purple aster thrive in locations with adequate sunlight, little precipitation, and between 1,000 and 11,000 feet of elevation, but within those conditions they can handle a great deal of adversity. They can survive in gravel pits, along highways, and in areas heavily grazed by livestock. However, at 270 Pope Lane, they do not need to struggle. Here they are provided all the sunshine they could ask for and most are a safe distance from the cheatgrass that covers most of the land and competes with the aster. The perfect resting place for a plant that is always on the move. Unlike many of the other native plants the residents of 270 Pope have so carefully cultivated, the purple aster came there on its own, as if it knew that was where it belonged. For, although the aster can tolerate even some of the worst impacts of human occupation, it would likely prefer not to have to put up such a fight. Purple aster has evolved to protect itself from the hungry mouths of cows, but not from one of their many followers, the highly invasive grass that has taken over the American West: cheatgrass. Purple aster can survive in the most barren conditions, often one of the first species to colonize a sterile landscape, but cheatgrass is making a valiant effort to rid the landscape of this spirited purple flower. The purple aster has tools to fight back, however. Because it is a late bloomer–the last colorful blossom to appear on this piece of land– it germinates at the same time as cheatgrass, allowing the aster to more effectively compete with the species that has so easily suffocated many of the aster’s native partners. Even so, the presence of cheatgrass greatly reduces the biomass of the hoary tansyaster above ground, though it does leave its roots intact. This may explain the height of these purple aster here on Pope Lane, coming up close to my waist, while elsewhere, often surrounded by cheatgrass, the plant barely reaches one foot.

It seems the purple aster, like many species, is well adapted to survive in the wide range of environments it finds itself in naturally, but falters when it is forced to compete with human-introduced species. Despite the obstacles the purple aster has faced for the last two-hundred years, it has not backed down. It can still be found all over the American West, its violet petals contrasting with the sea of yellow and green. It will not allow itself to be destroyed by humans or cattle, at least not yet.

By Kaitlyn Salazar